So, uh… did you happen to catch that Megalopolis trailer before it got pulled?

It feels silly to “in-case-you-missed-it” tiptoe around something this significant yet easily unnoticed. Which is how the internet works these days, by and large; most of what incites upset or confusion is only seen by a handful of people that various algorithms associate with said subject. To everyone else it never existed, and perhaps it’s better that way?

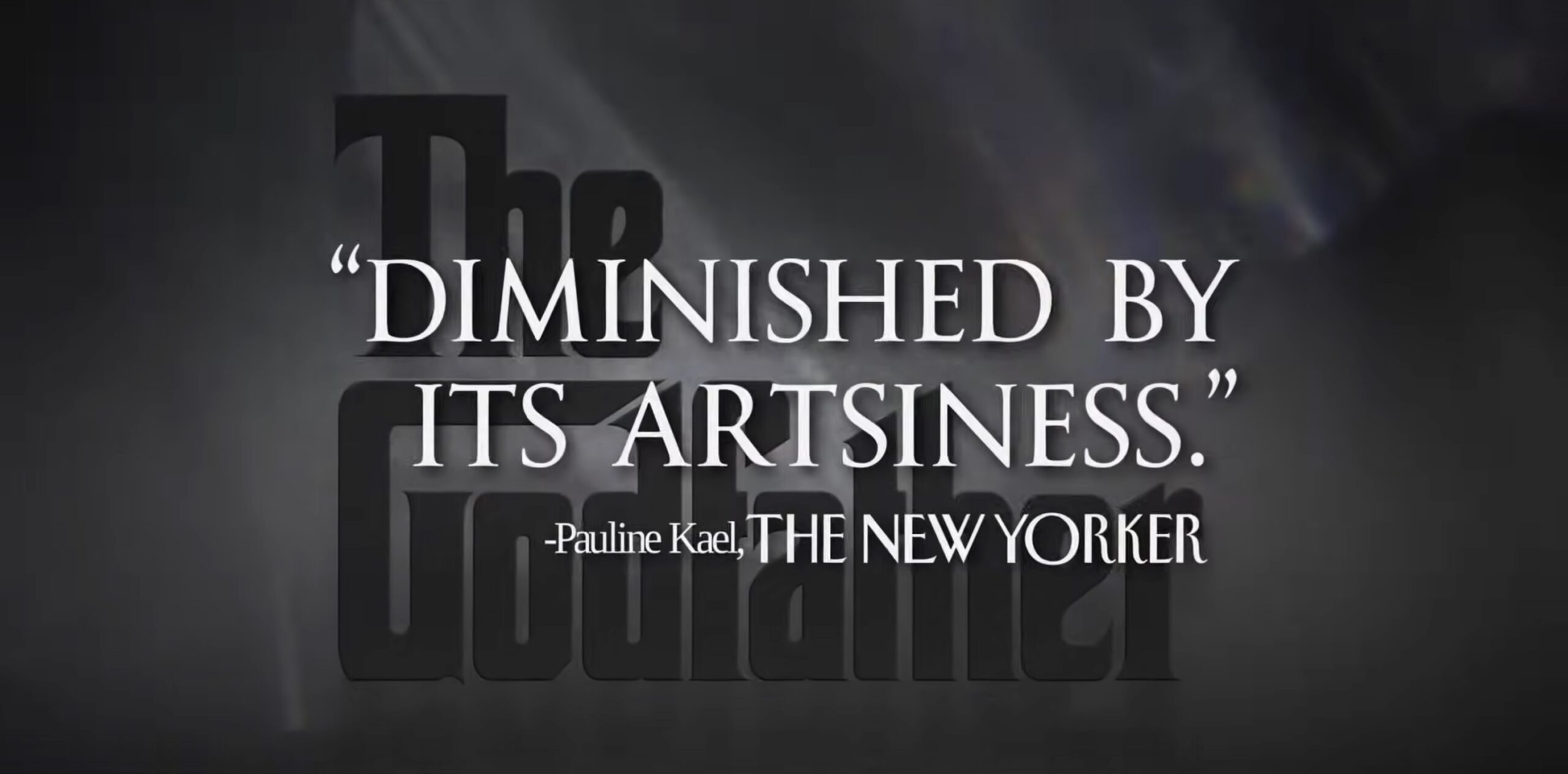

Except this was a truly wild screw-up that is so indicative of this specific moment in time, and it feels like it should be getting more attention. In case you missed it: The trailer for Francis Ford Coppola’s upcoming Megalopolis was released last week. It was a trailer that opened on an extremely awkward frame device—Laurence Fishburne’s portentous narration telling the viewer that “True genius is often misunderstood,” followed by a slew of quotes from film critics, each lambasting Francis Ford Coppola’s oeuvre. You know, movies that are typically trotted out with words like “masterpiece” in the same sentence. The stage is further set when the “Lacrimosa” segment of Mozart’s Requiem plays beneath all this, just in case you weren’t sure how to feel about it all. Then the trailer finally, pointedly, follows.

There are a number of reasons why this is a baffling move to open with. There’s the fact that most press is good press, ultimately; the more people talking about your movie, the more people are going to think about your movie, the more likely audiences are going to see it. (I am playing into this very problem right now, of course. You can’t get away from it.) There’s also the fact that Francis Ford Coppola, one of the most lauded filmmakers of the last fifty years, does not need defending from anyone. The choice to frame a trailer this way makes the director seem thin-skinned at best and actively nervous at worst, gilding the movie in the same sallow glow. We didn’t cover the trailer on this site because the exercise was, frankly, embarrassing for all involved.

That’s without mentioning that the quotes used in said trailer were all fake.

We’ve come to the second, far nastier piece of this clown-car escapade: It was promptly uncovered by Vulture that the quotes pulled from critical reviews for the trailer were either plumb made up, or, in the case of the Roger Ebert, pulled from a film review in no way related to Coppola’s work. Theories as to how this might have happened pinged around the internet in quick succession until the obvious and most egregious culprit was uncovered—the company responsible for making the trailer had used an AI system to gather quotes and, somehow, not a single human person thought it might be necessary to check those out before turning them into graphics that they slapped onto the very first wide-release trailer for the project.

People may use this as a teaching moment to warn everyone about the profligate misuse of AI in our day-to-day lives, as they should. This is a glaring sample of something that happens constantly now, every moment of the day: major errors going unchecked, prompts fed to systems that spout streams of misinformation, all of it being treated as the understandable growing pains of a new technology that will save corporations billions in (human) overhead. And this is without getting into the environmental cost of every single prompt fed to those systems. If this level of negligence is occurring around one of the most talked about films of the year, how do you imagine these errors are affecting every little corner of life without your knowledge?

Those conversations are important, but they weren’t the ones I was looking to have in the aftermath of this gargantuan clusterfuck that got an entire company publicly name-checked and fired by Lionsgate. The conversation I wanted to have was more along the lines of: Why was it so important to begin this ad campaign by shaming film critics for possibly not liking Francis Ford Coppola’s movies?

Yes, those critics generally like the films they were quoted to disdain. And that’s infuriating for a different reason, but it doesn’t begin to address the fact that it’s okay for critics not to like a movie, no matter how lauded that film may eventually be by the industry or the general public. Or that being against the zeitgeist doesn’t mean that the film review in question was bad in retrospect. Or that deciding whether or not Francis Ford Coppola is a “true genius,” as this trailer purported him to be, is not what art criticism is for.

Do we—collectively, societally—know what cultural criticism is? Because this trailer seems to prove the average person does not. The average person happening to include Francis Ford Coppola, by the way. Which feels great.

To proverbially lay all my cards on the table: I come from a family—biological and chosen alike—of artists. As a result, I’m accustomed to being surrounded by creatives, and I have considered myself a creative. Most of my friends are creatives in one way or another, as well. And it’s a vulnerable process making anything in this world, of course. A deeply personal one that makes even the kindest person inclined to defensiveness. Art is one way to share pieces of ourselves with the rest of humanity—if you feel a little angry that someone didn’t understand your art, didn’t understand you, I can hardly fault you for that.

But I’m also a critic. And in my time as a critic, I have been told, to my face, by people I care for, that critics are largely assholes who contribute nothing to the world. So this gets a little personal on all fronts, as you can see.

Do I think that skilled criticism can be an artform to itself? Absolutely. And with that in mind, perhaps I’m doing the same thing that this trailer was preempting: getting angry that people don’t understand those pieces of themselves that critics have laid out for inspection in their work. That trailer set the names of real people like Vincent Canby, Roger Ebert, and Pauline Kael out for ridicule. Canby, who made space for filmmakers like Spike Lee, Jane Campion, and Stanley Kubrick while aggravating the masses with cantankerous takes on many beloved films. Ebert, needing no introduction at all, the reason that most people today know film criticism (and many films, too) exists. And Kael, master of the field, who eschewed objectivity and insisted upon bringing the personal into critical voice. The idea that anyone would feel comfortable making Pauline Kael look out of touch when she was responsible for some of the best culture criticism of the previous century? It’s a lot to take on the chin, and let’s just leave it at that.

The trailer lobbed Andrew Sarris into this as well, a film critic who was a known proponent of the auteur theory of filmmaking—meaning that the trailer chose to drag a critic who is partially responsible for why we talk about Coppola with such reverence in the first place. Do you see what I’m getting at here? How wrongheaded the thinking behind this entire fiasco had to be at the conceptual level?

There is nothing wrong with reviews that are critical of Francis Ford Coppola. There is nothing wrong with reviews praising Francis Ford Coppola. What is wrong is that Coppola—or at the very least, the company distributing his film—seems very worried about what you might think if you run across the former rather than the latter. So they wanted to doubt all film criticism, before you’ve even bought your ticket to the theater.

And may I remind you that we are talking about a filmmaker who’s won half-a-dozen Academy Awards, three Golden Globes, two Palme d’Or, a few WGA awards, and owns his own winery? Not because it is relevant to the rest of my thoughts, but to point out that you’ve already been vindicated on this account, Mr. Coppola. This is like watching a prize fighter suddenly turn and go after a kid cheering him in the stands.

At the risk of beginning a lecture that I have no intention of finishing—cultural criticism is not for the artist who made the art. It’s also not really for fans as a broad spectrum group, unless you’re the kind of fan who can handle being told that art is imperfect. (It always is, and that can be feature rather than bug depending on your perspective.) And it’s been said before, but it always bears repeating: You don’t have to enjoy all or even most critics. They each have unique styles, perspectives, voices, and (very) personal bugaboos. They want different things out of the art they encounter, and finding critics who want the things that you want—or perhaps the critics who challenge you to want a little more or something new—is a good idea. Just like every movie won’t be brilliant, neither will every review or essay you find; we’re all just people too.

We’re people who get told every day of our lives that it “must be nice” to watch movies and television for work. (Which it’s not, by the way: It’s work. All work is work. Please don’t say that to us ever again.)

Do you know what art criticism is good for, by the way? Context. Genuinely, that’s the gig, in its simplest terms. We like to contextualize what we experience and think about it real hard. (Too hard? Yes. We can’t stop. Help us.) We like to tie the things we experience together and see how they relate to one another. And that context can come from a variety of disciplines: historical, thematic, logistical, scientific, theological, philosophical, political, literary, even emotional. Most critics don’t draw from the same set of wells for each piece they write, but they’re all important.

They’re important because it’s good to think about how our world fits together and shapes the things we create within it. No art is created in vacuum, which is something we should be thinking about all the time. Why? Well… it’s kind of adjacent to that whole “I can’t explain why you should care about other people” argument. I can’t explain why you should care about your own cultural context. As far as my brain is concerned, it’s pretty much all there is. It’s the only way we make sense.

As for Megalopolis… I’m not sure if I’ll be as awed by the film as this trailer hoped. But I can promise that when I watch it, it won’t be with any eye toward Coppola’s “true genius” that may or may not have been tragically misunderstood. And if I review it, I won’t be particularly worried about where my review will stand in the annals of criticism, years after the fact. Because I don’t do this work for history books or—future forbid—for the artist to notice me. I do it because I believe that work matters… and also because I couldn’t stop if I tried.