August began in Florence with friends, then we went to Worldcon in Glasgow by train via Cologne, then a week in Edinburgh at the Fringe seeing three or four plays a day, then back to Florence by train via Lyon. It was all excellent, especially sitting next to Naomi Kritzer at Worldcon when she won not one but two Hugos! My very first Worldcon was in Glasgow back in 1995, so it made it especially great to be back and seeing so many friends. So, a terrific month, but very busy. I read only ten books, but they were all very interesting, even the bad ones.

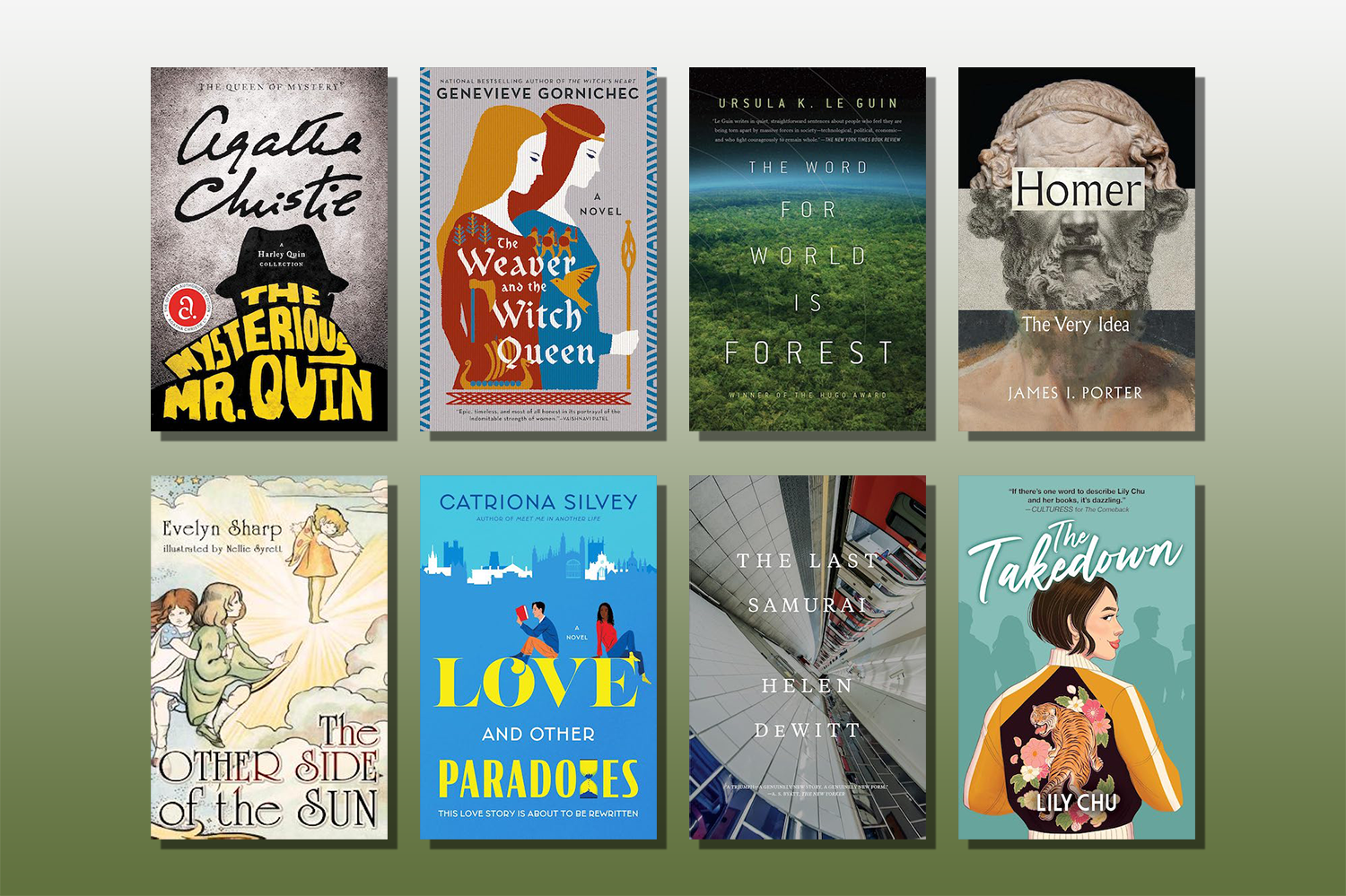

Homer: The Very Idea — James I. Porter (2021) Non-fiction, and fascinating. This is about the reception of Homer through all of time—that is, how people have thought about Homer himself and the Iliad and the Odyssey in their own changing context. The most interesting part is the meditations on authorship and authenticity. But I was very surprised that Porter didn’t even consider the Iliad as an anti-war story. He seems to believe it glorifies war and is positive about it, which I find as surprising as if someone was claiming the same for Wilfred Owen. I kept thinking he must intend to consider the anti-war message and responses to it in some later chapter, and then the book ended. Apart from this bizarre omission, it really is a terrific book, and very readable.

The Mysterious Mr Quin — Agatha Christie (1930) Right at the beginning of her career, Christie wrote these short stories that are mysteries but also fantasies. I keep trying to compare them to things (Dunsany, Wilkie Collins, M.R. James) but they’re not really like anything else. They’re definitely not ghost stories, or really any category of stories. If they’d proved as popular as her Poirot and Marple stories I wonder what both the fantasy and mystery genres would look like today, or whether we’d have a whole new genre that was… things like this. It’s so interesting to read them now and see what she was doing—they have the kind of characters and situations you expect in Christie, and then Mr Quin appears in their lives, sometimes very briefly and sometimes extensively. He is some kind of supernatural harlequin, drawing on a tradition I know very little about. He nudges his friend Mr Satterthwaite towards solving mysteries and preventing harm, sometimes protecting love or lovers, and sometimes speaking or acting for the dead. Most of the mysteries he solves are from many years ago, being solved, or resolved, at a satisfying moment. Each individual story stands entirely alone, but when Ada [Palmer] came across a single one of them in a Christie audiobook collection it was immediately apparent to both of us that this was a story belonging to SF/F, even though there was very little overt indication of that in the text of that one. Delightful to read and think about Agatha Christie, the fantasy writer that never was.

The Word for World is Forest — Ursula K. Le Guin (1972) Re-read. I hadn’t read this in a long time because while it’s great, it’s also sad and difficult and there’s a lot of message carried by a very thin skein of story, and because a lot of the book is from the point of view of a very unpleasant character. This is a book written during the Vietnam era that is directly about colonialism, slavery, and climate change. It isn’t subtle about them, and you have to be up for reading about these things happening on another planet in the future and seeing the parallels to our own planet laid out very starkly. So this is a significant book and a powerful one, but not an enjoyable read. Definitely a needed corrective to the kind of stories about humans colonizing the galaxy—Piper and Pournelle spring to mind—but somehow with less payoff than I want. I wonder if it’s too short—it was originally published in Again, Dangerous Visions and it might have been better at greater length and with more time spent among the culture of the Athsheans.

Rules: A Short History of What We Live By — Lorraine Daston (2022) An interesting analysis of the concept of rules over time, and the different ways of interacting with them. Daston introduces the concept of “thick” and “thin” rules, and of rules as examples (like precedents in a law court) and of discretion in interpretation. Well written and just flat out interesting. This made me think about everything from algorithms to the Rule of St Benedict, not to mention spelling and the way society organizes itself. There’s a really nifty section on the mechanical computations performed by human “computers” before machine calculations existed and how that was organized and how people thought about it. And modern ideas of how rules do and should work are very recent indeed.

A Tangled Web — L.M. Montgomery (1931) Re-read. Also known as “the one about the jug.” I read this book as a teenager, and remembered it only vaguely. I decided to re-read it after a panel about The Blue Castle which I know too well to re-read. So, most of this book is a mildly amusing novel about two large intermarried families in Nova Scotia and a lot of people who want to inherit a jug and sort out their lives. Things happen that are not very exciting, people fall in love, and out of love, and quarrel, and reconcile, and houses are weirdly significant in a way that is one of Montgomery’s quirks. It has a lot of characters but she keeps track of them all and reminds you who they are, and it’s the kind of quiet story of everyday people with nothing happening that you don’t often see. This was all I’d say about this book except that in literally the last paragraph it commits one of the worst examples of unnecessary and blatant racism I’ve ever had shoved in my face. I read this on a train in Switzerland and my travelling companions inform me that my mouth dropped open. Also, it was meant as a joke. Gah. Horrible. Read The Blue Castle, where her racism is not on display; do not waste your time with this.

The Weaver and the Witch Queen — Genevieve Gornichec (2023) Fantasy historical novel about three Norse girls whose fates are tangled. Pretty good on current research on the Vikings, definitely a feminist version, leaning strongly on both the sagas and archaeology. Excellent weaving magic well integrated into the world and the plot. Believable and memorable characters and relationships. Nifty trans character. I liked it, but maybe it suffered from being read in separated chunks while travelling and during Worldcon, because I never felt as if I warmed to it as much as it probably deserved.

The Takedown — Lily Chu (2023) Excellent chick-lit novel set in Toronto. (It’s chick-lit rather than romance by my definition because there’s as much about fulfillment through career as through love.) Chu is a terrific writer, funny, clever, interesting, she reminds me of Jennifer Crusie. This is about a woman working as a diversity advisor who really loves doing online puzzles, and meets a guy who also loves the puzzles. She has work problems and family problems and so does he. Fun and readable and tackling some serious issues well.

The Other Side of the Sun — Evelyn Sharp (1900) You know when Tolkien complains about the terrible pap sold as fairy stories to children? This is an example of that. The characters are all princes and princesses and have names like Princess Winsome and encounter tiny wymps and fairies who live on the other side of the sun and cause mild magical mischief. I’m sure Victorians found these charming, and hopefully they earned bright guineas for Sharp. (That term comes from Byatt’s Possession where a character is talking about selling fairy tales.) But this is a bad book in all ways, sentimental about both childhood and fairies, and lacking any edge at all. This is what Lud-in-the-Mist and Smith of Wootton Major were pushing back against. I read this so you don’t have to, and forever after I’ll be able to point to it when I need an example of how awful this kind of thing really is.

The Last Samurai — Helen DeWitt (2000) Re-read, I first read it in September 2020. This has nothing to do with the movie. It’s about an eccentric American woman in Oxford and London who has a son and decides to raise him like John Stuart Mill on languages and science from a very early age. She uses the movie Seven Samurai to try to provide him with positive male role models. He turns out very odd, and the second half of the book is about him trying to find himself a father. It’s funny, it’s gripping, it’s clever, and very readable. It was interesting re-reading this book knowing where it was going—though I’m not quite convinced DeWitt herself knew that. It has a wonderful voice, and wonderful observations about the world. There are no genre elements, but I feel it is a book whose audience is more likely to be found among SF readers than in the mainstream, just for the general geekiness and eccentricity of the characters. Beautifully written. Highest recommendation.

Love and Other Paradoxes — Catriona Silvey (2025) This is a time travel romance novel, sent to me by the editor who correctly guessed that I would like it. I did like it. I read it in one sitting when back in Florence and wanting to sit down and just read. I have a million genre niggles, which if I set them all out would make you think I hated it—but it’s just that thing that happens when a mainstream writer takes one of the tools of SF and uses it without realizing how worldbuilding works and everything connects. (I’d like to give Silvey an Ethics of Time Travel reading list.) Meanwhile, this is a well-written, grabby book with a lovely romance and very interesting thoughts on plagiarising your future life and work, with an excellent case of a time traveller from 2044 coping with the primitive world of 2005, and the kind of worldbuilding that falls over if you frown hard at it. It comes out next March and I commend it to your attention. I’ll make a note to remember to mention it again when it’s actually available.