State and federal officials have decided to curtail additional water flows intended to support endangered fish in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta this fall — a controversial step that is being praised by major California water districts but condemned by environmental groups as a significant weakening of protections for imperiled fish.

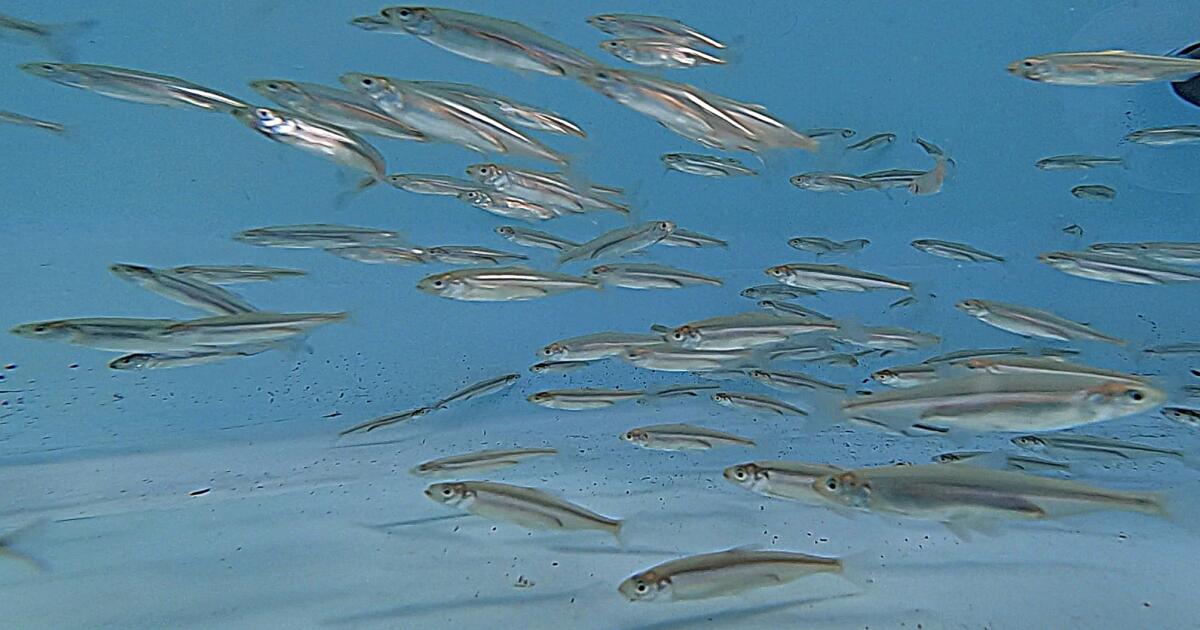

The debate centers on a measure that calls for prioritizing additional flows for endangered delta smelt, a species that has suffered major declines and is thought to be nearing extinction in the wild. The step of releasing a pulse of water through the delta in September and October is typically triggered when the state experiences relatively wet conditions, as it has during the last two years.

A coalition of environmental and fishing groups said these flows — called “Fall X2” water releases — are vital for delta smelt, and that the decision by state and federal officials to suspend the measure this year poses an added threat for the fish.

“At this time next year, we may be looking at the extinction of a fish species that was once incredibly abundant,” said Gary Bobker, senior policy director for the group Friends of the River. “And it will have been completely preventable.”

Managers of large water agencies disagreed, calling the requirement outdated and saying it wouldn’t help the delta smelt population recover. The State Water Contractors, an association of 27 public agencies, said the change this year will preserve needed supplies in reservoirs.

The organization praised what it described as California’s “adaptive management,” saying in a press release that recent research has indicated these water releases “are not providing the benefits to Delta smelt that were originally hypothesized in 2008.”

“We are extremely pleased with the decision to rely on the full body of scientific evidence to assess the value of Fall X2 releases,” said Jennifer Pierre, general manager of the State Water Contractors.

She said the decision ensures the same protections for fish and water quality as the existing 2019 biological opinion issued by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the existing permit for the state’s pumping facilities in the delta.

“We applaud state leaders for their continued commitment to science-based decision-making,” Pierre said.

The State Water Contractors and large agricultural water suppliers — including Westlands Water District, San Luis and Delta-Mendota Water Authority and the Friant Water Authority — had urged state and federal agencies in an Aug. 21 letter not to carry out the water releases this year.

They argued the additional flows should not occur for several reasons, including “peer-reviewed scientific conclusions indicating that the measure is ineffective for its stated purpose.”

Pierre and other managers wrote in the letter that recent monitoring surveys for delta smelt have yielded “very disappointing results” and that “only one smelt has been observed in recent weeks.” They said it’s possible that despite ongoing efforts to protect the fish, “there may not be a remaining, measurable population of Delta smelt to benefit from a Fall X2 action.”

Pierre also said the measure has taken a significant toll on the state’s water supply in prior years, such as 2023, when operators of the State Water Project “sent 600,000 acre-feet to the ocean” to implement the requirement — more than the total annual water use of Los Angeles. This year, state officials said, discontinuing the additional environmental flows in October could enable California to deliver as much as 150,000 acre-feet of additional water.

Water from the delta is pumped through the aqueducts of the State Water Project and the federally managed Central Valley Project, supplying farms in the San Joaquin Valley and cities across Southern California.

The federal Bureau of Reclamation and the state Department of Water Resources operate the water systems in the delta under the 2019 biological opinion, which during the fall of wetter years requires the agencies to “either provide additional flows, known as Fall X2, or take other similar or more protective measures to improve the habitat of Delta smelt,” said Mary Lee Knecht, a spokesperson for the Bureau of Reclamation.

“During September, Reclamation and DWR implemented both required Fall X2 outflow provisions and additional voluntary measures to improve Delta smelt habitat in Suisun Marsh and will now off-ramp the flow requirement in October,” Knecht said in an email to The Times. She said the Bureau of Reclamation and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have concluded that this “will provide similar or better protection for the smelt” and will allow scientists to test how effective the water releases are.

The state Department of Water Resources said officials have also used gates in the Suisun Marsh to “maximize suitable habitat” for the endangered fish in the delta. The department said in an email that modeling by federal wildlife officials indicates having the additional outflows in the delta in October “is not a critical driver of Delta smelt survival.”

State wildlife officials have approved the approach.

Environmental advocates recently wrote to federal and state officials urging them not to suspend the additional flows in the delta. They said the additional water in the delta in some years has played an important role in preventing the extinction of delta smelt, and that not making the water available “would be irresponsible and indefensible.”

“The situation of Delta Smelt is dire, and its record low population levels call for strong interventions by the state and federal agencies responsible for preventing its extinction,” leaders of several groups said in one letter.

In a recent article, Bobker and Jon Rosenfield, science director of San Francisco Baykeeper, said a wealth of scientific research shows that larger flows in the delta during the fall continue to be important in preventing the extinction of delta smelt.

“California habitually fails to enforce environmental laws designed to protect our aquatic ecosystems,” they wrote. “Following the state’s lead, federal agencies skimp on environmental safeguards and waive the meager protections they do offer any time protecting the public’s fish, wildlife, waterways, and water quality, gets in the way of diverting more water to meet California’s seemingly unquenchable demand.”

The debate coincides with parallel ongoing struggles over how California should adapt its water policies to protect fish populations in the state’s rivers in the face of drought and climate change.

Other fish species have also suffered declines in recent years. Regulators have banned commercial and recreational fishing for Chinook salmon along the California coast for the last two years in an effort to help the species recover.

Environmental and fishing groups said the increased exports of water from the delta this fall pose serious concerns.

Barbara Barrigan-Parilla, executive director of the group Restore the Delta, said government agencies are “changing the rules to weaken Delta protections for powerful special economic interests,” including large water suppliers and the agriculture industry in the San Joaquin Valley.

“The rules protecting fish only work when they are enforced,” said Chris Shutes, executive director of the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance. He said the current approach amounts to mismanagement and is “making the rules optional each time water contractors clamor for more water.”