[ad_1]

I am haunted, however lightly, by one pivotal instance of feeling like a creep as a teenager. I was at my best friend’s house for the thousandth time, and she was fast asleep on the old waterbed we shared whenever we stayed at her place. I was awake because sleeping through the night has never been easy for me, and the hot sticky rubber of a waterbed didn’t help. Even though we were exhausted from staying up until 4am filming Buffy reenactments on her dad’s old camcorder, I was awake; my best friend was not. And I looked at her and felt a sharp, undeniable stab of possessiveness overtake me as I looked at her sleeping face. I was awake, and I was being creepy, and I was deeply ashamed of myself.

We were in high school, and she had started dating boys; a terrifying crevasse only I could see was steadily forming between us. I knew, on a deep inexpressible level, that I was some kind of queer; I knew she was not. And I knew that I was a disgusting little monster for developing these jealous, unspeakable feelings. In fifth grade, my mother had sat me down in her bedroom for “the talk” after a boy passed me a love note and she found it. She told me that to love someone means wanting to have sex with them, and suddenly affection seemed incredibly sinister to me. She also added, “I will love and support you even if you are a lesbian, but I hope you aren’t a lesbian, because if you are you’ll have a miserable life.” I internalized these messages, especially the latter one. I refused to be gay because I did not want to be miserable.

I refused to be gay, so instead I was a creepy girl staring at her “normal” best friend.

I have never, ever spoken about this. I write about it now because I am older and tired and I know that most queer kids go through similar and far worse agonies throughout adolescence. Queer kids are told, both directly and indirectly, not only that their affections are wrong, but they are disgusting, life-ruining, and disturbing.

This also appears to be the case for Yoshiki, the teenage protagonist of The Summer Hikaru Died. Yoshiki lives in the genuine inaka, stuck in the cicada-laden, mountainous countryside of Mie prefecture. His world is composed of hot summer days, thick green forests, studying, and, most vitally, daily hangouts with his best friend Hikaru.

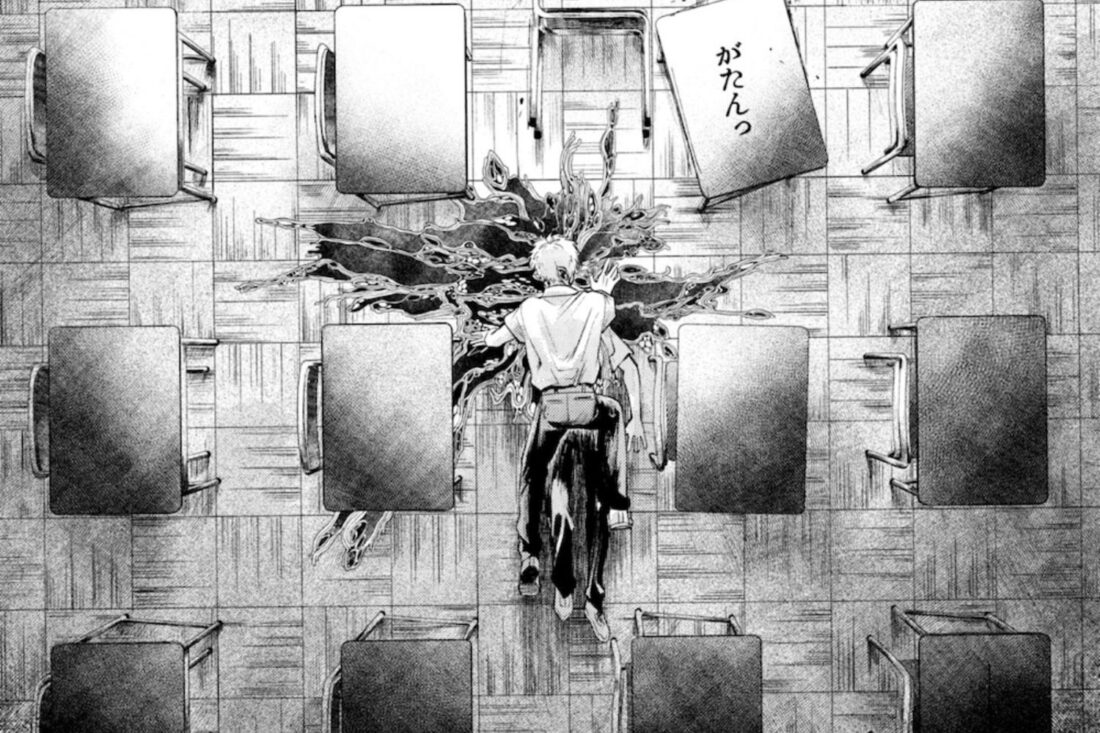

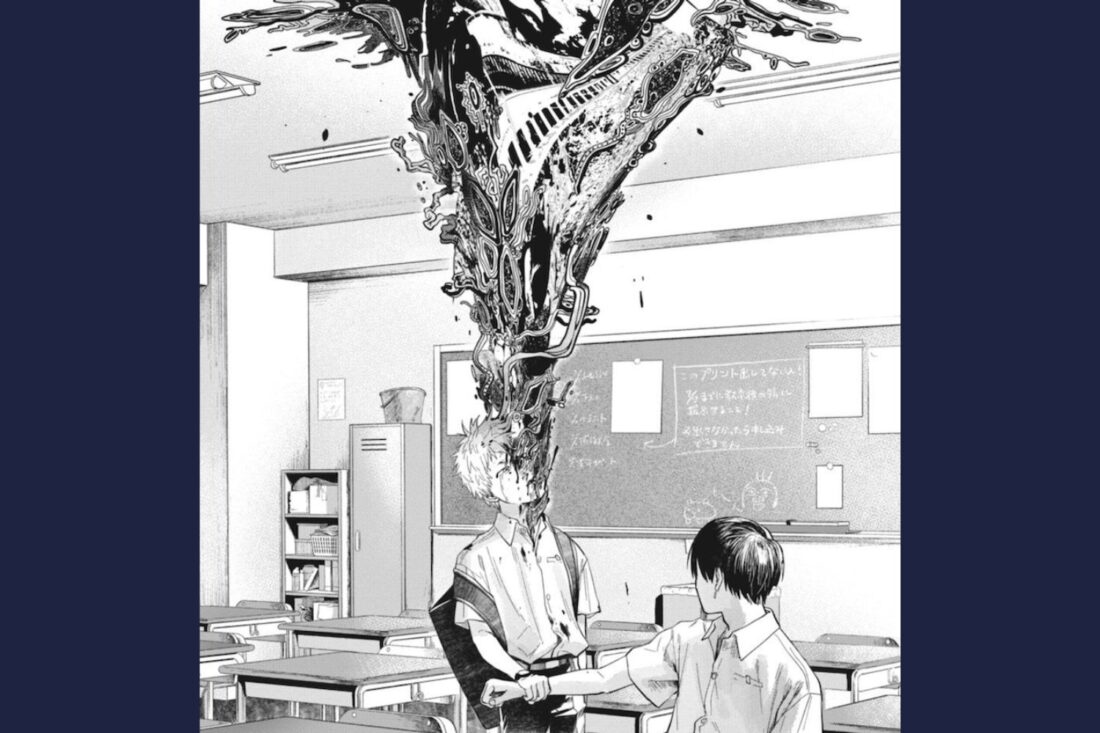

The trouble is that Hikaru is actually dead. He goes missing in the mountains in the late winter, and the thing that spends summer days with Yoshiki, though it has Hikaru’s face and voice and memories, is not Hikaru. An arcane mountain creature akin to a god has taken up residence inside Yoshiki’s best friend; a Lovecraftian mass of worming spirals and fleshy paisley writhes beneath his skin. Yoshiki, who knows Hikaru better than he knows himself, is not fooled. In the manga’s very first chapter, he confronts not-Hikaru. “You’re not really Hikaru, are you?” Upset and tearful, the innards of Hikaru’s replacement leak from his left eye socket and he throws his arms around Yoshiki. “Please don’t tell anyone!” he sobs. “I don’t want to kill you!”

Well, that’s a pretty brutal coming-out.

But Yoshiki is, on some level, reveling in the embrace. And Yoshiki, despite it all, has no intentions of sharing this horrifying secret. Because the monster occupying Hikaru is similar enough to the real Hikaru to ease his grief but different enough that he relies on Yoshiki to feign humanity. And this new Hikaru is deeply infatuated with Yoshiki in ways that the real Hikaru never could be. Though it disturbs Yoshiki to acknowledge it, in a way, this devotion from Hikaru is more than Yoshiki ever dared dream of.

Given the choice between not-Hikaru and no Hikaru, there’s no choice at all.

With The Summer Hikaru Died, fledgling mangaka Mokumokuren is doing more than expanding the definitions of what BL and horror manga can become; they are also writing one of the most painfully relatable, beautiful but disturbing queer coming-of-age stories I have ever been privileged to encounter.

The Walls Have Eyes

Mokumokuren started writing The Summer Hikaru Died when they themselves were a teenager, but it was not until they shared panels on social media after their high school graduation in 2021 that the publishers of Young Ace Up offered them serialization. Like many mangakas, Mokumokuren prefers to keep their identity and gender private, but I find their choice of pen name compelling. Mokumokuren is the name of a yokai (I wrote a lot about my yokai fixation in my Natsume Yuujinchou essay). The name means “many eyes,” and these yokai are watchful eyes that grow on neglected shoji screens and tatami mats.

In Kubitachi, the claustrophobic village Hikaru and Yoshiki call home, it’s hardly any wonder the boys feel like they are being watched. Small towns can be incredibly invasive and gossipy, and Yoshiki’s parents are notorious for their abusive arguing, which gives the neighbors plenty of fodder for gossip. This, combined with the unspoken feelings Yoshiki is coping with, reinforces the idea that their hometown is a place that must be escaped from. Even as a young boy, he confesses to Hikaru that he longs to run away to the city. Hikaru, playing in a stream, disagrees, because he enjoys the country life. To comfort Yoshiki, he tells him, “Whenever you feel like you wanna go to the city, you should come to my place!”

Hikaru does not know what those words might mean to Yoshiki, the doomed hope they instill in his young heart. Years later, when not-Hikaru relies on Yoshiki to keep his monstrous nature a secret, his words are direct and indisputable rather than suggestive. He shoves Yoshiki to the floor and climbs on top of him, enacting the most sinister kabedon. Not-Hikaru truly means it when, black abyss pouring from his facial orifices, he cries: “I know it ain’t right but I still like you! And I can’t stop my feelings!”

After, he literally recomposes himself, withdrawing the abyss. He begs Yoshiki, “Please don’t hate me.” But Yoshiki could never hate not-Hikaru, no matter how terrifying he is. That’s the whole dilemma.

The thing about fear and romance is that they both rely on tension; under Mokumokuren’s brilliant pen, that tension is exploited. Is Yoshiki gasping beneath not-Hikaru because he is terrified, or because he is aroused? Is it both? Is not-Hikaru desperate to coat his beloved friend in his creepy innards to smother him in darkness, or in affection? When Yoshiki gazes at raw chicken during home economics class and remembers how those innards felt like cold meat, is he sweating at an uncomfortable memory or, well, a horny one?

If all this weird speculation is making you uncomfortable, that’s perfect. Then you’ll have some inkling of how these characters feel.

While the story is mostly focused on the central pair, other characters also have roles to play. A classmate with a mild sixth sense knows something is off with the pair of them. And there’s Rie, a local woman and occasional exorcist who indulged a similar monster from the other side to a disastrous end. She warns Yoshiki that he shouldn’t remain friends with not-Hikaru for long, because if he does, they will end up… mixing. But even though she warns him, she’s not surprised the warning goes unheeded. She’s been there.

What teen in the world hasn’t heard warnings about some friend or another being a terrible influence? Yoshiki, who has long since internalized his queer feelings as disgusting, decides that the negative influence is mutual. It is wrong to spend so much of his time and energy on not-Hikaru, and wronger still to touch him. But Yoshiki is helpless to resist. In the P.E. storage room, he plunges his hand into the gaping pit that opens up in not-Hikaru’s torso and at first it feels awful, and then it feels good.

The encounter is strange and a little nauseating but also undeniably erotic. Such forbidden interactions are only as horrific as they are sensual. They serve as troubling and true analogies for the experiences an infinite number of queer kids have lived through.

Scenes like this, for my money, firmly establish The Summer Hikaru Died as a masterpiece in the making. Weird as it may seem, countless readers will agree: it is hard not to root for this fucked-up young couple. Sure, one of them is essentially John Carpenter’s The Thing with a much cuter person suit. No one’s a picnic during puberty. And somehow, there’s an unspoken, unsettling optimism underneath it all.

You can’t bury your gays if the gays are already undead.

He’s Growing on Me

After Yoshiki establishes that not-Hikaru an incomprehensible being from elsewhere, he can begin to reevaluate not-Hikaru as his own person. Not-Hikaru is emotional and codependent, and delights in new experiences. Though he has Hikaru’s memories of festivals and fireworks, not-Hikaru has never experienced these things for himself, so those memories may as well be a movie. While the mystery is still being solved, it is clear that the being inside not-Hikaru spent decades or centuries or longer as a cursed god, ritually trapped on a mountain. It was incapable, of enjoying even the humble charms of rural life. Yoshiki realizes that not-HIkaru is, in some ways, like a child. He clings to Yoshiki like a toddler, sobbing into his shirts, begging for affection and forgiveness: “I wish creepy stuff would stop comin’ out of me when I get all shook up.”

Unfortunately, like very small children, not-Hikaru has yet to develop empathy. Initially, he kills a villager who recognizes his inhumanity. He visits her home at night and later she’s found dead and there’s no mystery there. Yoshiki suspects as well, and when at last he asks not-Hikaru directly, Hikaru sees no reason to lie. “Bein’ dead, bein’ alive, is there really that big a difference?” When Yoshiki vomits in response, not-Hikaru recoils. He does not understand, but he is trying to.

Cats kill mice and fish eat worms. Every damn creature on the earth defends itself when cornered. When not-HIkaru acts, it is usually to defend his secret or to protect Yoshiki. He is so far almost incapable of being duplicitous. He is honest when confronted, but his memories are garbled, and he himself is confused about what manner of creature he is. Though he lacks empathy, his affections for Yoshiki, however wrong and intense, are genuine. It’s a toxic codependency but not a heartless one.

It helps that not-Hikaru’s point-of-view is nearly as prominent throughout the manga as Yoshiki’s. Because we are privy to Hikaru’s thoughts, we empathize with the creature he has become. He can see the dead and the living too; he sees through people to their souls and thinks that Yoshiki’s soul is beautiful. Souls exist separately from their mortal bodies, he says. So is it any wonder that he doesn’t understand the fuss when someone dies? For so long he had no body, and even now he is an undead creature, and if the soul carries on, why are people so upset?

Yoshiki wonders, “What qualifies a person to be themselves? Their memories? Their cells? Their experiences?”

So far, the manga has made an excellent case for the “experiences” angle. And if not-Hikaru is growing as a person, becoming more empathetic and less violent, he is doing so by choice. Isn’t that laying the groundwork for a great protagonist?

They Haven’t Killed the Cat

An aside: it’s a tired trope that only true masterpieces like Alien avoid: any cat who shows up in a horror movie will be killed for dramatic effect. I can report that so far, thirty chapters in, the monster in this story has not killed the cat. It sounds minor, but I think it is another deliberate choice, indicative of how wonderfully subversive this work is as a whole.

Mince-aniki is a fat neighborhood stray who gets spoiled by the local butcher and doted on by all those who stop by the local corner shop. While Mince-aniki is fond of Yoshiki, who is known to be good with animals (and eldritch beings, too, apparently), the cat, like all chubby furballs worth their salt, senses immediately that not-Hikaru is a monster. He reacts accordingly, hissing and biting his outstretched hand. The first time this happens, Mokumokuren draws a furious gleam in not-Hikaru’s eyes. Oh great, I thought while reading, wincing with dread. Now it’s time to cut to the scene where a cat has been slaughtered.

But color me surprised. Instead, in a later chapter, not-Hikaru tries once more to woo the stubborn cat, this time guided by Yoshiki. They entice him with an irresistible tube of Churu. “I really want to touch that cat!” not-Hikaru declares. At last, he has his chance, and he chooses to poke Mince-anikie in the side. The cat is mortified and vanishes. Yoshiki laughs, saying, “That’s some way to touch him!”

“I bet he liked the old Hikaru,” not-Hikaru says, disappointed. But Yoshiki says otherwise.

“Nah, he hated him too.”

As of this writing, Mince-Aniki remains alive, fat, and fluffy.

It’s Catching

Near the end of volume four, an exorcist named Tanaka is called to Kubitachi village to root out the monster that has descended from the mountain. The trouble with the eldritch being abandoning the mountain is that its very essence attracts creatures and spirits from the other side, and now those creatures are drawn to the villages.

If that isn’t another fantastic allegory: the fear that one “aberrant” individual will attract more aberrant individuals. Unfortunately for the people of Kubitachi, unlike queerness, which is decidedly not contagious, the arrival of not-Hikaru does seem to herald the arrival of many more creatures from the other side. A wig monster invades Yoshiki’s family bathroom, and a ghost haunts the local railroad crossing. More will come, for as long as not-Hikaru remains in Kubitachi. But not-HIkaru can’t be killed by traditional methods, as Yoshiki discovers the hard way. And Yoshiki still doesn’t want him gone.

Consensual Corruption

“…wanna try feeling it again?” not-Hikaru asks, after Yoshiki finds himself staring at the cold meat in home ec class. And Yoshiki relents, and later the tentacles inside not-Hikaru crawl up his arms and thinks, “This has to be all kinds of wrong, but why does it feel so good?” But when Hikaru lets the darkness overwhelm Yoshiki a little too much, Yoshiki asks him to stop. Not-Hikaru does so immediately, face burning in shame.

See, this otherworldly creature, though murderous and emotionally stunted and lacking a soul of its own, is a decent enough person to understand consent. Even from the very beginning, when the eldritch creature first discovers the original Hikaru’s body on the mountainside, bleeding from a head wound after a fall, it waits for an invitation. The cursed god only takes over Hikaru’s body after Hikaru, with his dying wish, asks it to: “Take my body and look after Yoshiki.”

This series is ongoing, and an anime version has just been announced, and more horrors and wonders are to come. When Mokumokuren first published The Summer Hikaru Died, they described it as a Boys’ Love story. That label, however fitting, cannot encapsulate how the manga has continued to defy genres, subvert themes, and exceed expectations with visionary aplomb. We are told that those who mix with the darkness will attract more darkness. Yeah, yeah, okay; if you’re a closeted boy and an unfathomable undead monster falling in love, you’ll have a miserable life. Somehow, despite warnings like this, gay people keep on falling in love.

Though I cannot guess how this story will end and I know that it would be foolish to assume the ending will be anything but tragic, I cling to some twisted hope, just as Yoshiki and not-Hikaru cling to each other. Maybe these two, whatever else they destroy and become, will get out of Kubitachi and make for the big city, and live how they want to live. Who cares if all the creatures from the other side wreak havoc in their wake; cities are large and monstrous already, and neither of these kids asked to be what they are. Maybe it’s wrong of me to daydream about such an unlikely, cheesy, romantic ending. But you know what? I’m not a teenage girl in love with her best friend anymore. I’m a tired, asexual adult who has learned, time and time again, that what’s “wrong” is often subjective. And maybe, for once, it would be nice for the creepy eldritch horror to unlive happily ever after.

Note from the Author: Right, so I originally said this article would be broadly about body horror, but this manga is so damn good that it deserved its own dissection. Instead, expect the body horror essay next time, as a sort of post-Halloween companion piece!

One of my favorite aspects of this manga is how it defies preconceived notions of what Boys’ Love stories can be. A few years ago, I wrote a YA novel that was soundly rejected by my own publisher because it was a creepy horror story and also a queer coming-of-age story. I was told it was too difficult to mix those genres; YA audiences wanted either a gay love story or a horror story, but not both at once. Welp, I would like to think the world has evolved, and now Mokumokuren has done what I could not, and done it better than anyone I have ever seen. Are any other queer, genre-defying manga or anime on your rosters?

[ad_2]

Source link