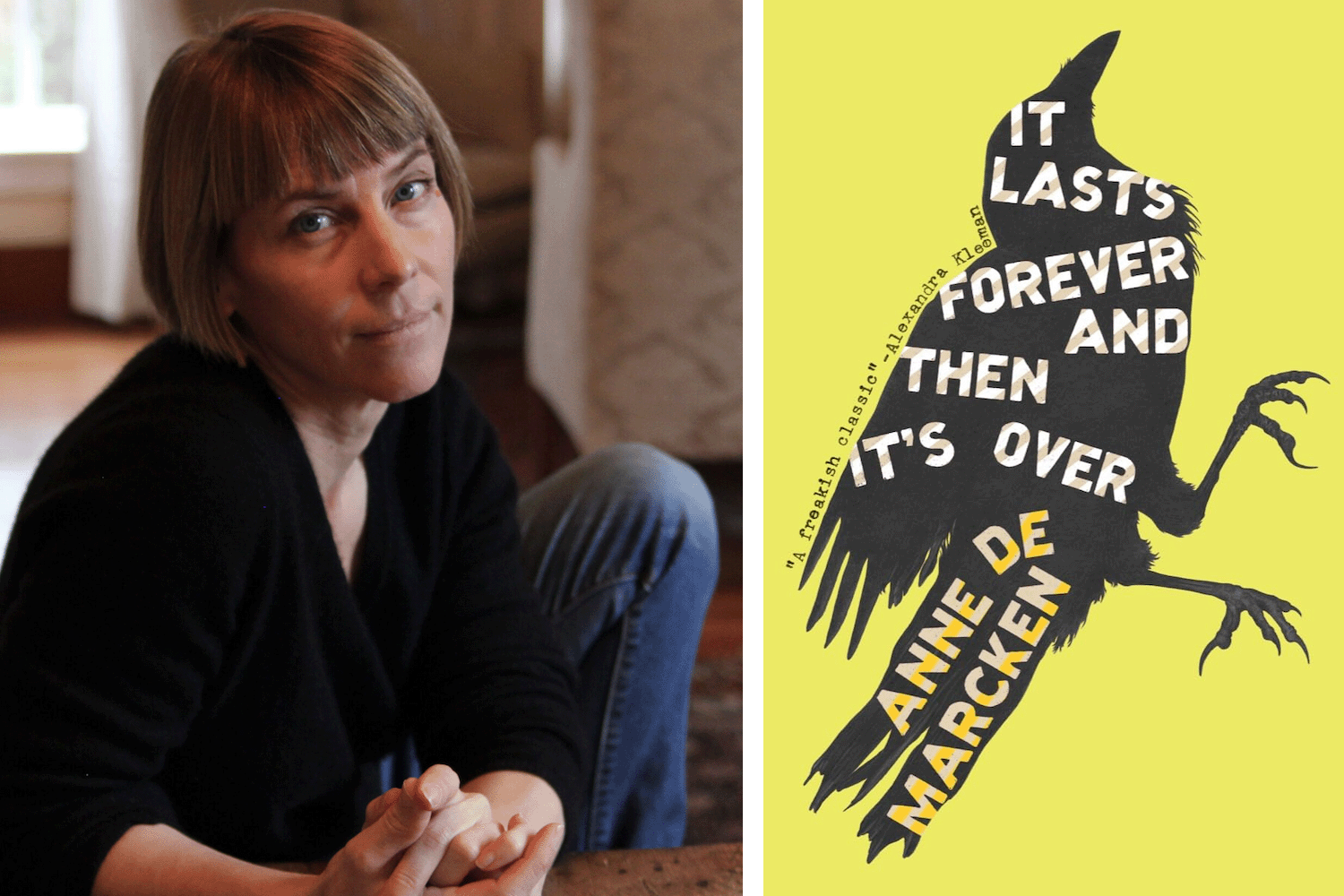

I am thrilled to speak with Anne de Marcken, this years recipient of the Ursula K. Le Guin Prize for Fiction, which celebrates work of imaginative fiction that shares the ideals and themes of Le Guin’s work, including “hope, equity, and freedom; non-violence and alternatives to conflict; and a holistic view of humanity’s place in the natural world.”

De Marcken’s novella, It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over is not your average zombie story—with exquisite prose, it explores hunger, grief, memory, and our place in the natural world. The unnamed protagonist’s afterlife includes both a reverence for nature and a deep sense of loss as she recalls moments of her life before and the love she has since lost. This year’s selection panel, which consisted of authors Margaret Atwood, Omar El Akkad, Megan Giddings, Ken Liu, and Carmen Maria Machado, called the novel “[h]aunting, poignant, and surprisingly funny, Anne de Marcken’s book is a tightly written tour de force about what it is to be human.”

Congratulations on receiving this year’s Ursula K. Le Guin prize! Can you tell me about your relationship with Le Guin’s work? Do you see any thematic overlap between her work and yours?

Thank you, Christina! I am honored and deeply moved by receiving this award. It matters a great deal to me that it bears Ursula K. Le Guin’s name. Her writing—and her thinking about writing—are important to my own, though on the surface our work may not appear to have much in common. I think I share with her a kind of optimism that is so intimate in its orientation that it can survive grim realities. A relational optimism. Also I think our work has in common a place-based-ness—a sense that all of the climatic, sentient, leafy, mineral, moldering, fleeting, and permanent-seeming aspects of where we are go into who we are. It is an ecological way of apprehending human existence, which also is political in that it challenges anthropocentrism, and, at the level of narrative, the idea of the hero and what is heroic.

In your artist’s statement, you describe yourself as being the same artist no matter where you’re sitting. How does your work as an editor and publisher affect your work as a writer, and vice versa? What about your work in other mediums?

It’s nice to be reminded of that artist’s statement. That kind of thing can be removed from the day-in-day-out reality of work, but actually it does feel pretty true and helpful to remember. In the same paragraph, I say that I have two desks, and that I move my chair back and forth between them—which is literally the case. Often I am caught up in feeling that I am spending too much time at one desk or another, one kind of work taking my attention from another, but really both desks are crowded with books I’m referencing for writing projects and publishing projects (sometimes the same books), with manuscripts I’m writing and the ones I’m editing, with sketches, index cards, bottles of ink, paint brushes, stones…and cats. So my study is a bit more boundaryless than I suggest, as is my creative practice. I think a lot of interdisciplinary artists can feel frustrated by the apparent discontinuity of their work from project to project and over time. But even though artists—like everyone else—are expected to fashion a legible and coherent persona (through artists statements, for example), how useful to creative work (or life) is a coherent persona…or an incoherent one, for that matter? So maybe a combined effect of these different ways of working has been to focus me on the work at hand, rather than on who or what I am—writer, filmmaker, printmaker, editor, publisher, teacher, etc. I tend to reach for the medium, the tool, the collaborator, the way of working that best serves a particular creative impulse. I started the The 3rd Thing (the press) in response to an urge I have to foster things that are bigger than I am, things that get away from me, to be in community, and also to do work that meets a need. Am I answering the question yet? Maybe not. The influence of one way of working on the others is just so vast and varied and nuanced, I hardly know where to begin…and then how would I stop? Fundamentally, in whatever the medium or role, whether I am tuning into the voice and language and material technologies of someone else’s work or of my own, the work requires me to listen very closely. It requires patience, stillness, discernment, exactitude—a rigorous and spacious attention to the congruity of intention and execution…to the wobbles and kinks, the moments of hesitation or distraction, that can interfere with a work achieving its wholeness, and to the emergent possibilities that give it life. Also it all requires a certain wildness—almost recklessness. Practicing this at one desk, so to speak, makes it more possible at the other…and in the rest of life.

Author and one of this year’s prize selectors Ken Liu has spoken frequently about the relationship between speculative fiction and metaphor—that speculative fiction is where metaphors are made true and tangible. Your narrative seems very aware of the metaphors at play. How would you describe your approach to making metaphor real in the world of this novel?

In one way, the book is an attempt to un-metaphorize the zombie in order to reclaim what we might like to disavow or relegate to the realm of dystopian fantasy. The received trope of the zombie is so familiar that I had to spend no time at all establishing the unreal, and instead focused on trying to represent the familiar, the small, the subtle, the ordinary. This is where my attention is drawn naturally. Rather than verisimilitude—real-seeming-ness—I am concerned with accurately representing existence as I know it. Less speculative than fantastical, the book hinges on the uncanny—the familiar unfamiliar…the sense we all have had that something is out of place and without reference, which is almost the opposite of the metaphorical premise. Really, I am uneasy with metaphors. I am—in life and in my writing—very caught up with the difficult effort simply to perceive and then to convey what is, and while metaphor can illuminate, it also has a way of obscuring two things at once—the thing you are attempting to represent and the thing you are comparing it to. The characterization and externalization of the “worst” parts of ourselves as monsters, for example, obscures our complexity rather than illuminating it. It reifies ideas of good and bad, worthy and unworthy, kin and outsider, human and sub-human, self and other, around which power consolidates and sustains itself through systematized alienation and oppression. The peril of metaphor emerges as a theme in the book, related to the instability of identity, the ambiguity of boundaries between one thing and another, and the possibility of losing connection with things as themselves…and each other. None of which is to say that I disagree with the idea that fiction is a figurative province, but that my approach is reflexive—that is, it refers to itself—I attempt to deliberately and transparently perform—reveal, question, subvert—my own metaphor/meaning-making.

How would you describe your narrator’s state of being at the beginning of this novel?

Neither alive nor dead. Undead. She is outside the processes of energetic exchange: growth, decay, uncertainty, choice, compassion, contingency….

This book grapples with some pretty big questions. When you sat down to write, what were the questions you were initially interested in exploring, and did any others pop up during the writing process?

I was curious about zombies. Our monsters are reflections of ourselves at any given cultural moment. They tell us what we find immanently threatening. We grotesquely distort the unfamiliar or any group that embodies our failings or jeopardizes our status. We carve out and externalize abject aspects of ourselves, shaping a malignant “other” against which we can fight heroically. I am deeply distrustful of this maneuver. I have always been skeptical of both righteousness and evil (and heroism) and have tended to be on the side of the monster, but zombies never held any fascination for me. I began to wonder why. What was I too ready to overlook about myself? I became curious about this ravenous cannibal and what it says about us—about me. Looking for what animates the zombie, so to speak, I focused first on hunger. Why would something that does not need to eat crave so powerfully? I could relate to that, but there was more. Hunger seemed like an expression of rage. Surely, I rage. What, I wondered, is the source of my rage? At the time I was reading Judith Butler’s The Force of Non-Violence. Following up on something Butler writes in that book about the way language can be used to dehumanize, I stumbled across a talk they gave in 2014 (“Speaking of Rage and Grief”). It completely unmade and remade me. In it, she quotes the preface to Grief Lessons, Anne Carson’s translation of Euripides. There Carson writes, “Why does tragedy exist? Because you are full of rage. Why are you full of rage? Because you are full of grief.” I feel this so deeply, so personally. Grief is a thing we avoid so avidly that we put it away from ourselves with disastrous, violent consequences. I am deeply grateful to Butler and Carson for this insight. It led to an exploration of the ways we are made up of our relationships to people and places and what happens to us when we lose them. This is the question at the heart of the book: how much can we lose before we, ourselves, are lost—and then what happens?

Buy the Book

It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over

It struck me that many of the memories our narrator recalls are about being in nature, or her relationship with particular locations. How did you approach balancing a story about supernatural hunger–which can be so destructive—with a bountiful and lush natural setting?

It’s a contradiction we live with here in the United States and in much of the world. We are of this place and yet act on it—extract from it, engineer it, divide it, own it, sell it…consume it—as if we are super-natural, as if it is separate from us and subject to our impulses. This is a violent way of existing, and by now it comes very easily to us in spite of the obvious—if cognitively confounding—consequences. Chief among these, climate change. Anthropocentrism (and its attendant mechanisms—colonialism, capitalism, the many and various ways we rank worth, i.e. human-ness) is killing us and all that we hold dear. It was important to me, as I wrote, to stay in contact all the time with a feeling of connection and love so that I had available the sensation of what it is to lose connection and love, to be without them. I feel powerfully and most readily connected to the “natural” world. My grief over the loss of plant and animal species, of the seasons as I know them, of quiet, of darkness, of places I love and places I have only imagined—this underlies every moment of ease and happiness or even discomfort and impatience. Writing with specificity about place, insisting on the realism of a setting I know well…this kept me in touch with the central question of the book, and the existential stakes of it.

Hunger is a driving force in this narrative, and appears as both a physical and spiritual sensation. Why did hunger become a narrative touchstone for you?

The zombie’s perverse expression of hunger is one of the most recognizable and consistent traits of the trope, and to me the most confounding. Can they even digest what they eat? Their hunger is uncanny. It is senseless and pointless. It is vestigial—a kind of phantom urge that is impossible to satisfy. And yet they are compelled by it. Like any compulsion, it is a signal: something else is going on here. It was an easy signal to follow, since I can relate to hunger, and, as I attempted to understand this monster and to identify with it, hunger took me places I might not have gone otherwise. In particular, it made me value horror in a way I hadn’t previously, not as a genre, but as an essential element of human existence and human narratives. Now it is right up there with beauty and ambiguity.

How would you describe your narrator’s relationship with her body?

Evolving and complex. On one hand, she feels liberated from the constraints of life, and relates to her body in a much more material and even plastic way than someone concerned with mortality or pain. On the other hand, she characterizes the loss of pain as the loss of her humanity. On a third hand, she is deeply ambivalent about humanity as a category, so that loss is rueful. She is bemused, unsure where exactly to locate her self as distinct from anything—everything—else.

One of the (many) lines that struck me was “the end of the world looks exactly the way you remember. Don’t try to picture the apocalypse. Everything is the same.” It felt particularly apt given the current state of the world. How do you approach writing a story set after an apocalypse or major disaster while the world we currently inhabit feels so dystopian already?

That line is, in essence, an instruction to myself as much as to the unnamed “you” of the story or to the reader. It is very difficult to grasp this moment. We are in the midst of an extinction event that we caused, but also “life goes on.” To write about this, to suggest that this is the catastrophe we fear, that the very last of a thing—the last summer, the last day with the person you love, the last of a particular kind of bird—does not announce itself, I attempted to drain descriptions of hyperbole and to resist world-building exposition. When I deployed apocalyptic images as such, I attempted to frame them as nostalgic conceptions of the future that are as removed from reality as the chipper theme song of “The Jetsons”—uncanny coincidences of popular imagination and lived experience.

What clarity, if any, is there to be found in the afterlife? How does death change your narrator’s outlook?

I think of the afterlife as the mythical province of the dead, and this book is concerned with the experience of undeadness. I haven’t spent concerted time imagining the afterlife, so I can’t say what are the differences and similarities. While the afterlife is debated as a matter of faith—as if it is either real or not real (I come down on the side of not real), the popular version of a zombie (as opposed to the Haitian Vodou zombi) is fantastical; their unreal-ness is a settled matter. This is one reason the zombie was so valuable as an imaginative foil—it exists outside my belief system and funded an exploration that was unencumbered by the constraints of possibility or the rhetoric of faith (though some of the undead in my novel do attempt to situate themselves in a religious framework). I think the death that has changed the narrator’s outlook is not her own. She is grieving the loss of someone—“you”—she loves. That death has rendered her foreign to herself…or perhaps known to herself in a way that is so foreign as to be utterly undoing. Her efforts to avoid encountering the pain of that loss and of her continued existence—and eventually her determination to have exactly that encounter—this results in doubled and dislocated and unresolvable perspectives on herself and others, that are, I think truer—or closer to accurate—than what she approached in life.

What advice would you give your 14-year-old self?

Don’t ever sell your books. That’s all I can come up with. Really I think I’d rather get advice from that younger self than try to give it. She knew things that I struggle to remember or value in the same way. She knew better how to sit still, how to rest, how to sink into what gives her pleasure, how to suspend disbelief, how to follow an impulse without judgement. I have a lot of questions for her.