[ad_1]

For a good deal of this election cycle, Gavin Newsom acted very much like a person wanting to be president.

He traveled the country and ran TV ads. He raised billboards and debated Florida’s Republican governor on national TV, just a few weeks before Ron DeSantis’ campaign crumpled in a humiliating heap.

The not-really campaign was never an actual, serious run for the White House. First Joe Biden and then (o, bitter pill!) his sometime friend, sometime rival Kamala Harris stood in Newsom’s way. It was more like California’s restive governor was letting his ego loose for a bit of an off-leash romp.

Things changed after Nov. 5, following Donald Trump’s triumph and California’s notable shift toward the center-right on election day. Suddenly, Newsom started appearing in places such as Bakersfield, Redding and Colusa, among the ruddiest parts of red California.

It’s something the governor should have done a long time ago, rather than strutting and preening on the national stage. There are millions of Californians — politically outnumbered, geographically far-flung — who have long felt derided or ignored by Sacramento.

But give credit where due. Newsom is showing up.

And if he’s interested in really, truly running for president in 2028 — when the Democratic contest looks to be a wide-open affair — it’s not a bad place to start.

The program Newsom has been pitching of late, the “Jobs First Economic Blueprint,” has been in the works for some time.

In promotional materials, the governor’s office describes the program as a “bottom-up strategy for creating good-paying jobs and regional economic development.” The plan follows lengthy consultation with locals in 13 parts of the state and aims to streamline programs and spur economic growth through a series of tailor-made initiatives.

The unveiling in the red reaches of California was no accident.

With Trump’s victory, Democrats have begun to reckon ever more seriously with their diminished standing among union members and working-class voters and the party’s catastrophic collapse — decades in the making — across rural America. There’s a new urgency “to solve problems and meet people where they are,” as David McCuan, a Sonoma State political science professor and longtime student of state politics, put it.

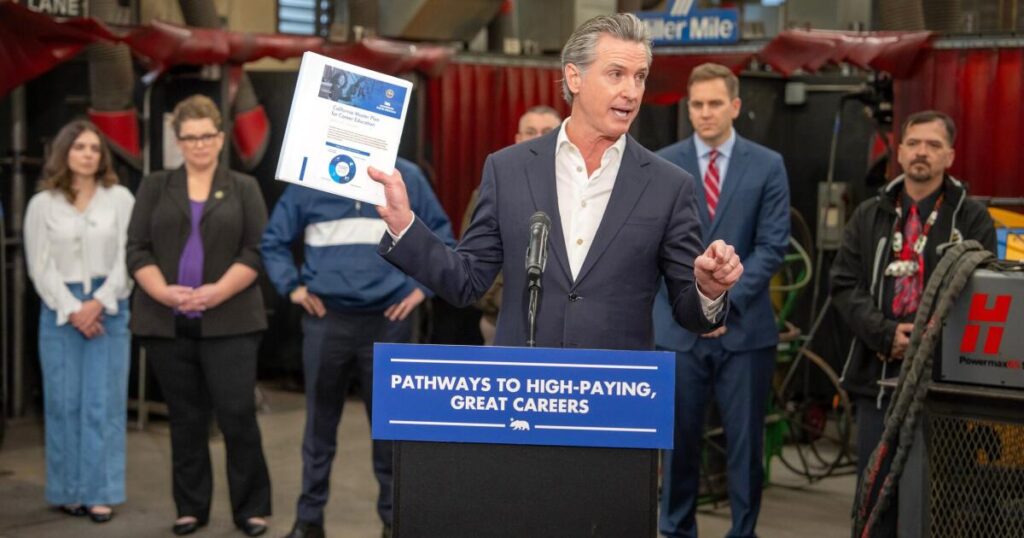

In California, that means venturing beyond the politically comfortable climes of Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area into the hostile interior, and extending what Newsom described during a recent appearance in Redding as “an open hand, not a closed fist.” (The event at Shasta College, unveiling a plan to create better job opportunities for those without college degrees, even drew the rare presence of a GOP lawmaker, local Assemblywoman Heather Hadwick.)

It’s exactly what the governor should be doing. Seeing and being seen in red California sends a message to fellow Democrats as they puzzle out their way forward. More importantly, it tells those living outside the state’s big cities and sprawling suburbs they matter and their cares aren’t being overlooked.

Those close to the governor say Newsom is in a much better place now than the pouty, sulky space he occupied in the months after President Biden stepped aside and anointed Harris as his successor.

It’s not just the sidelining — for the time being anyway — of the vice president, who clearly bested Newsom in their unspoken, years-long competition. There is also a renewed sense of purpose with Trump returning to the White House and California poised to emerge, once more, at the vanguard of the political opposition, with Newsom in the lead.

No one, perhaps not even the governor himself, knows whether he will attempt a genuine, full-fledged try for the White House in 2028. But there are things he can do in the meantime to better position himself if he decides to do so.

Chief among them is ending his term a little over a year from now with a sheen of success. And that means spending more time in places like Ione and Newcastle than Iowa and New Hampshire. (You can find those tiny towns in Amador and Placer counties, respectively.)

There may be no small element of fantasy in the talk of Newsom as a serious presidential contender.

Having just lost the White House with one San Francisco-incubated nominee atop their ticket, it seems quite unlikely that Democrats will turn to Newsom, another of that ilk, to be the party’s savior four years hence.

But who knows? With a twice-impeached convicted felon preparing to take the presidential oath for a second time, it’s impossible to rule anything out.

Newsom’s red-state rambles may end up having no effect whatsoever on his political future.

But they can’t hurt.

[ad_2]

Source link