Weird things about (real) physics drew me to science fiction in the first place. I attempted to duplicate Young’s double slit experiment in elementary school in my bedroom using an index card and a flashlight. I begged my parents to let me mail-order lasers so I could take up holography in high school; my parents wisely said no. My boyfriend-now-husband had concerns about my interest in that hypothetical vacuum bubble instanton experiment where, if there exists a lower-energy-state parallel universe to our own, it would have the side effect of destroying our universe.

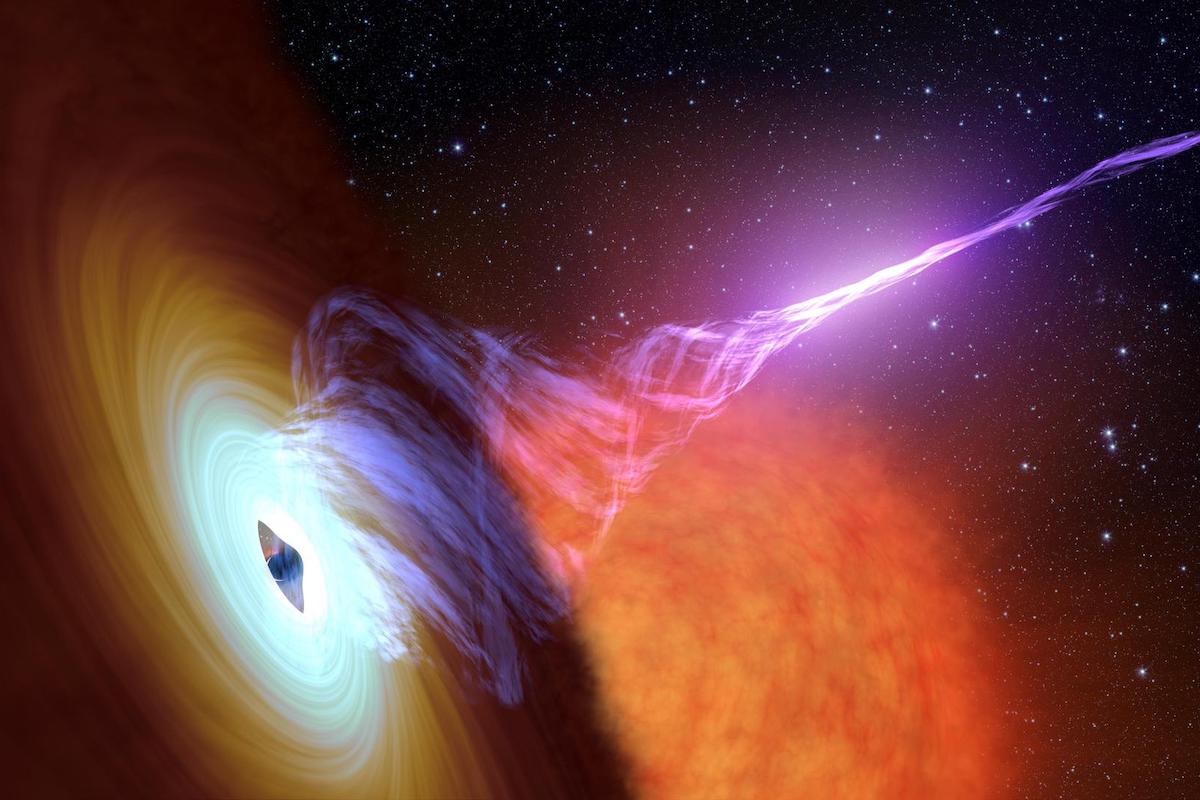

These days I destroy fictional worlds. My YA novel Moonstorm (Delacorte) is the first in a mecha space opera trilogy and features outré physics, including temporarily breathable aether rather than vacuum, and gravity maintained through ritual. Moonstorm runs off the sci-fantasy metaphor that conformity = LOTS OF GRAVITY, but too much nonconformity = WORLDS FLY APART. I absolutely go to the MOAR GRAVITY = BLACK HOLE place with this book, although fortunately, real-world physics and high school do not work like this! But let me tell you about some books I read as a kid that inspired my space opera and which explore physics ideas in nifty ways.

Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonflight

When we were young, my friend Gwyn got into McCaffrey’s Harper Hall trilogy and was excited about fire lizards, but Dragonflight was the one I read first. A major plot point involves dragonriders who have mysteriously vanished from the past, leaving the present-day world of Pern in danger when they’re needed to defend the land from an interstellar spore. The heroine, Lessa, figures out that someone—herself—time-traveled via dragon ride to bring them to her present (their future).

What’s interesting here is that Einstein’s insight that our three dimensions of space and one of time are woven together in a four-dimensional space-time fabric is relevant to the plot. Lessa lives on a lost colony where advanced science has been lost, but it’s established that dragons can teleport between places, which then implies that they can also travel between times, an epiphany Lessa comes to through clues she laid for herself.

Joan D. Vinge’s The Snow Queen

The Snow Queen was my first encounter with consequences of relativity as a plot point. Moon is a sibyl of the world of Tiamat, ruled by the eponymous Snow Queen of whom she is unknowingly a clone. Access to Tiamat is limited by a destabilizing nearby star that shuts off access to the interstellar community for 150 years at a time—and Tiamat is valuable to the offworlders because it’s the source of an elixir that halts aging. The Snow Queen created Moon as part of a plan to free Tiamat from offworlder exploitation. Moon inadvertently leaves Tiamat and discovers the truth of the offworlders’ designs during a journey that takes weeks for her but several years for people back on Tiamat, including her estranged lover—an example of relativistic time dilation exploited narratively for plot and interpersonal implications. (Hint: Time dilation does not help Moon’s relationship problems, but in fairness, the lover doesn’t help Moon’s relationship problems.)

Incidentally, I enjoy Lewis Carroll Epstein (physicist)’s explanation of time dilation in special relativity as, approximately, “You’re always traveling, but some is in the space directions and some is in the time direction, so if you go faster in the space directions, you slow down in the time direction.”

Greg Bear’s Blood Music

I read the short story version of this in an anthology back in high school and chased down the novel later. I have run into people espousing extremely bizarre and not even wrong interpretations of quantum physics (think “healing energies and vibrations”), but the late Greg Bear was a physicist!

In Blood Music, a scientist creates and makes contact with sentient nanoscale biological organisms (noocytes). At first the noocytes “improve” their human hosts in a neighborly nanovirus way. Then the improvements go to the creepy body horror place. Then the noocytes multiply so wildly that they take over the world. It’s a “mad science, whoops” story, but not without moments of grace and humor: The carefully timed appearance of a can opener made me cry.

That isn’t the brain-breaking bit! The brain-breaking bit is where the noocytes have become so numerous, their density so high, that their amassed, intentional control of the observer effect can collapse quantum states to the point of active reality warping. As you might imagine, the question of whether reality-warping nanocritters and humans can coexist, with or without dubcon body modifications, is a major source of tension.

John E. Stith’s Redshift Rendezvous

My first encounters with Stith’s science fiction were via his satiric sci-fi gumshoe tales “Naught for Hire” and “Naught Again.” Redshift Rendezvous is seasoned with that sardonic wit. It’s also a murder mystery with a spectacular premise: It takes place aboard a starship where, during hyperspace travel, the speed of light is 10 m/s as opposed to 3×108 m/s. Relativistic effects, such as red-shifted light, are now visible at human running speeds; you can even see light travel when you flip a switch. At first, the death of a crew member on this ship is ruled a suicide, but it emerges that there are hijackers with a darker agenda, and the story follows the ship’s first officer attempting to stop them on this unusual battleground.

The book rigorously explores the implications of this counterfactual leading up to the solution in a way that I found extremely satisfying. Thematically, the slowness of light means everything that’s seen is notably in the past, and the past remains alive and visible in an eerie way. This idea is also famously explored in Bob Shaw’s story “Light of Other Days,” although the counterfactual mechanism there is different: “slow glass,” a material with a refractive index so high that it takes years for light to pass through it, and which reveals a years-old tragedy captured as though in amber.

William Sleator’s The Boy Who Reversed Himself

Surprise! You thought I’d name Sleator’s Singularity. I inhaled all the Sleator I could find during middle school. This one features a boy who has figured out how to reverse himself by walking through a fourth spatial dimension; he gives himself away to a girl because the reversed version of him has his hair parted on the other side. They become friends, and all’s fun and games in the fourth dimension until they encounter hostile fourth-dimension aliens and have to outwit the would-be invaders of Earth. There is a delightful detail that reversed ketchup tastes intriguingly weird. I suspect now that there would be possibly fatal biochemical implications involving chirality (left- vs. right-handed version of molecules), but chemistry is not my field.

I imagine the antecedent to this book is Edwin A. Abbott’s Flatland, a mathematical exploration of spatial dimension as well as a satire/critique of Victorian culture and its hierarchies, including the roles of women. But Flatland’s narrator, A. Square, didn’t have to contend with a hostile visitor from a higher dimension!

This book and Flatland were the first time I thought about dimension in a mathematical sense. Innocent of linear transformations or orientability, I spent a happy afternoon at the chalkboard in physics class a few years later trying to figure out how the left-right reversal worked.

All of these books are fabulous and tremendously educational: Follow in their footsteps, and you, too, can earn a reputation for destroying readers!

Buy the Book