Languages give us greater access to people and knowledge, and the more of them we know, the more power they give us by expanding that access. Knowledge of languages also determines which ones survive, which ones are lost, and which ones dominate over the rest. Everything we do today, from obtaining an education in a coloniser’s language to resisting (or working with) AI, centres around the undeniable potency of languages.

How do SFF authors visualise the role of such power? Here are five takes on what it means to translate, to preserve languages, and to use language for preservation…

Babel, or the Necessity of Violence by R.F. Kuang

Perhaps no list of SFF about translation would now be complete without Kuang’s powerful speculative exploration of the role of language in the British Empire’s growth, with the translation gap acting as a literal source of magic that powers the economy of the colonialists.

From the outside, the Royal Institute of Translation—or Babel—is a haven for linguists and translators. Robin, an orphan from China, is trained by Professor Lovell to study at the Institute, for there is power in speaking a tongue one knows since birth, as opposed to learning it at a later age. Multilingual people, Robin learns, are a resource the empire uses to expand its reach. As he meets other students who have similarly been brought to Babel for their diverse and “exotic” mother tongues, Robin finds himself questioning the role of his language in enabling colonisation. What can a powerless student from a colony do to fight the empire? Can words—language—actually make a difference?

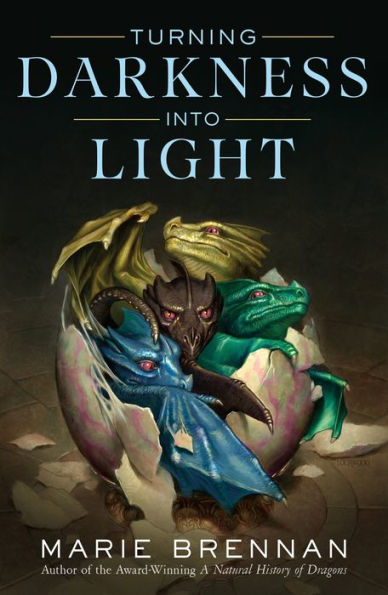

Turning Darkness Into Light by Marie Brennan

Audrey Camherst, the granddaughter of the pioneering dragon naturalist Isabella Camherst, wants to live up to her family name through her work on decoding and translating a set of Draconian texts, which she is working on with her close friend and colleague, Kudshayn, who has his own battles to fight with society. The project is not just a scholarly undertaking—as the duo uncover the meaning of the text, they find that there are people who don’t want the translation completed, and who are willing to do anything to twist the text for their own ends.

A standalone sequel to Brennan’s wonderful Lady Trent memoirs, this book marvellously combines linguistics, archaeology, folklore, and politics, and makes me wish, every time I think about it, that I’d discovered sooner that one could make a career in languages and translation.

“Diamonds and Pearls” by JL George

When you speak the common tongue, diamonds fall from your mouth. When you use the Old Tongue, which was once forbidden and is now largely forgotten, you get pearls. Osman knows only swear words in this vanishing language, but he speaks them still so that he can collect the pearls—one for each new word he learns. It is his little rebellion, in which he is joined by another, a partner not just in love but also in language preservation. But love, like language, is never static. Can the Old Tongue be enough in keeping a relationship intact, or will the affection slowly disappear just like the language did?

“The Lexicographer and One Tree Island” by Akhim Alexis

Accompanied by a corbeaux that brings him news from other places, Tonie spends his time on the single mango tree on a tiny island, a very small part of what used to be the Caribbean island of Gahara. He doesn’t want the Gahara language to disappear, so he spends part of his day writing down in his notebook every word he can remember, leading the corbeaux to name him a lexicographer.

When one day there’s news of other human survivors, including one who speaks Tonie’s tongue, Tonie has to decide—should he leave One Tree Island to join them, or should he stay here, potentially losing the chance to connect with someone who can help him preserve his language?

“A Pale Horse” by M Evan MacGriogair

The world is going to end. Our protagonist watches the horizon over the waves, looking for something, though she’s not sure what, as she thinks about the silences in the world, the fire alight in the Amazon, the species going extinct. As she heads home, she spots a car window with a phrase scribbled across it, reading “seeking a friend for the end of the world,” along with words from a language she was just thinking about. She writes back with her number and receives a sound file, a piece of music that seems to reflect a deep understanding of what she’s been looking for. In return, she sends the stranger a video of the view from her window.

So begins an exchange in recording and sharing the beauty of the world. It’s a beauty that infuses pictures and music and language, connecting people without needing meaning, offering a way to preserve the world, its sights, its music, its languages. I have read many short stories about both beauty and the end of the world, but I have never read something so deeply immersive, so gentle, so optimistic, something whose prose has the feeling of gauzy curtains in the summer or a hazy winter’s walk. Beautiful.