[ad_1]

The late California Sen. Dianne Feinstein was among the wealthiest members of Congress, with a Bay Area real estate empire valued in the tens of millions of dollars.

Whoever wins the Nov. 5 election to be California’s next senator will have a very different financial picture.

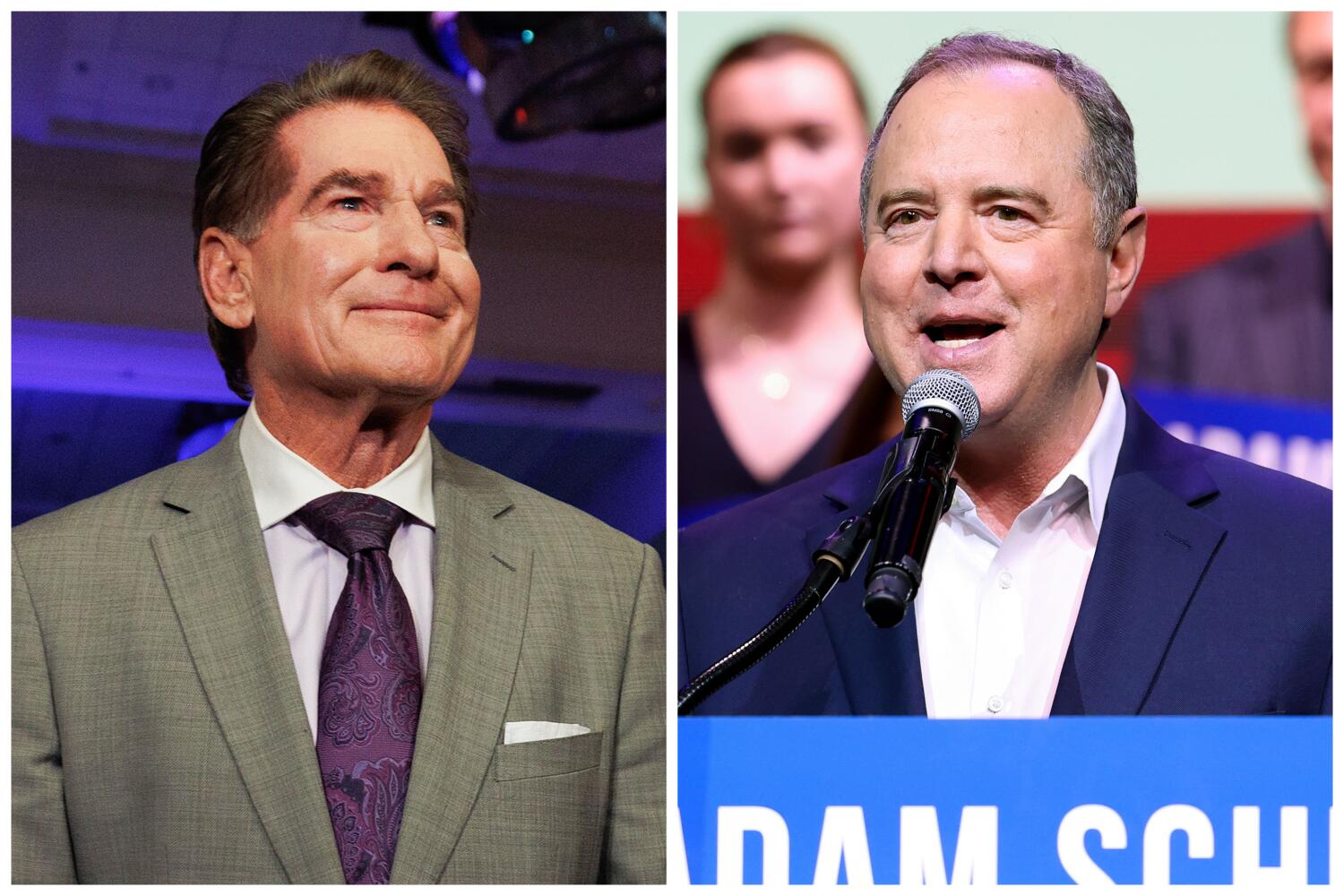

Democratic Rep. Adam B. Schiff of Burbank, 64, has worked for the government since graduating from Harvard Law School, working as a law clerk for a U.S. District Court judge, in the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles, for the state Legislature in Sacramento and, since 2001, the House of Representatives.

Republican Steve Garvey, 75, graduated from Michigan State University and played first base for the Los Angeles Dodgers and the San Diego Padres for 18 years.

Since retiring from baseball in 1987, Garvey has worked as a paid spokesman for more than a dozen companies, including two that ran afoul of federal regulators. He has painted himself as a successful businessman, but financial disclosures and court filings show that he is hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt.

Schiff’s staid investments

Schiff earns $174,000 as a member of the House of Representatives.

In an August financial disclosure, Schiff reported earning between $43,310 and $134,000 in additional income last year through capital gains and stock dividends — some shared with his wife, Eve — and royalties from his 2021 book, “Midnight In Washington.”

Schiff’s investment portfolio is worth $1 million to $2.37 million, and includes mutual funds, exchange-traded funds and shares in Apple held by his wife. He has mortgages on a Burbank condo and a house in suburban Potomac, M.D., with joint balances between $350,002 and $750,000.

Schiff’s net worth places him squarely in the middle of California’s congressional delegation.

He ranks far below California’s wealthiest representatives, Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Bonsall) and Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco), whose estimated net worths topped $200 million in 2023. But he is still far ahead of members whose net worths are hovering near $0 or below, including Rep. Norma Torres (D-Pomona) and Rep. Mark DeSaulnier (D-Concord).

Schiff’s investment strategy has gradually shifted from individual stocks to mutual funds that hold shares in many companies, a Times review of Schiff’s financial disclosures show. His wife’s Apple shares, valued between $100,001 and $250,000, are the only remaining stock in their portfolio.

Between 2007 and 2009, Schiff sold hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of shares in the pharmaceutical giant Wyeth Corp., which manufactured Robitussin and Advil. The company was acquired by Pfizer in 2009, and Schiff sold his final Pfizer shares in 2015.

He also offloaded shares in 2015 from industries that Democrats have more recently eschewed. He sold up to $100,000 worth of shares in Altria, one of the world’s largest producers of cigarettes, and up to $60,000 of shares in gas and oil companies, including the pipeline company Kinder Morgan.

Since the publication of his 2021 book, Schiff has reported making up to $2.05 million in royalties over three years. The book details his work on investigations into the Trump administration and his work as chief prosecutor in Trump’s first Senate impeachment trial.

Garvey’s scant assets

In a disclosure filed in August with the U.S. Senate, Garvey reported earning $75,174 last year and another $66,295 from speeches, memorabilia signings and other events. Garvey also reported between $60,000 and $130,000 in income from retirement plans, including a Major League Baseball pension.

Garvey and his wife reported very modest assets. They have less than $30,000 in their checking accounts and one investment in the stock market: shares of Nvidia Corp., the Silicon Valley chipmaker, which are worth less than $15,000.

The disclosures make no mention of the sprawling, Spanish-style ranch where the couple lives in Palm Desert.

Garvey said a decade ago that the couple purchased the house from his mother-in-law when she planned to downsize, telling an interviewer that the house “was really home to all the grandchildren and a place that we thought was special, so we bought it from her.”

Riverside County property records show that the home’s deed was held by Garvey’s mother-in-law before being transferred in 2006 to Sisters in Christ LLC. The Utah company names Garvey’s sister- and mother-in-law among its managers, records show.

The home’s tax bills are sent to the limited liability company, in care of Garvey’s mother-in-law, to an address in La Quinta, Calif., property records show. The Sacramento Bee was first to report that the home’s property taxes are paid by Sisters in Christ.

Last year, the Coachella Valley Water District placed a lien for $1,715.23 for “delinquent charges, penalty and interest” on the Palm Desert house. The bill was sent to the limited liability company.

Garvey’s campaign did not respond to questions about his finances, including his real estate holdings, investments and debts.

Financial skeletons in the closet are not inherently disqualifying for a candidate for public office, said Jessica Levinson, a professor at Loyola Law School and the former head of the city of L.A.’s ethics commission.

The question, she said, is to what extent Garvey is willing to be forthcoming with the public in explaining his debts, including how he amassed them — particularly as he seeks a public role that involves “some level of financial acumen.”

“How people conduct their own personal financial affairs does not always have a direct connection to how they perform in their professional lives,” Levinson said. “But some people will say, if you can’t pay your own debts, can we trust you to keep our financial house in order?”

Hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt

Garvey is hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt to private creditors and the government.

Some debts date to the 1990s, Garvey’s first decade after retiring from baseball, where he was earning $1.25 million a year with the Padres. He faced mounting costs for legal fees, spousal support and payments for children he fathered out of wedlock.

Garvey said in a court declaration in the 1990s that he suffered a “financial disaster” when the Internal Revenue Service disallowed tax deductions he claimed in connection with an investment in the early 1980s, The Times reported in 2006. The IRS decision meant he owed $937,000 in back taxes, penalties and interest, he said.

“Do I expect to pay every debt? Do I want to? Absolutely,” Garvey said in 2006. “The day I’m able to be debt-free is the day I’m going to be the happiest guy around.”

Garvey has been sued at least seven times for unpaid debts, including by the lawyers who handled the legal wrangling over one of his child-support cases. The law firm claimed Garvey owed nearly $200,000. Garvey agreed in a 2004 settlement to pay $100,000. Whether the debt was satisfied is unclear.

Garvey, his wife and his companies have been named in hundreds of thousands of dollars of state and federal and tax liens, the extent of which was first reported by Politico. Garvey’s disclosures with the U.S. Senate list up to $750,000 in tax liabilities.

Garvey said earlier this year that he was working to pay off his tax debts. The couple paid off several liens from the early 2000s and put $25,000 toward their 2006 lien, records show.

But there is no sign that their more recent debts have been cleared. The couple has accrued more than $275,000 in IRS debt since 2010, including a lien levied last year for $25,742.37 that stemmed from unpaid taxes from 2012, according to Riverside County tax records.

Spokesman for a company with ‘Ponzi scheme’ ties

As California’s housing market boomed in the mid-2000s, Garvey took a job as a celebrity spokesman for an Orange County mortgage broker.

National Consumer Mortgage was run by Sam Favata, a former Cal State Fullerton baseball star who had been friends with Garvey for more than three decades, Garvey later said. Favata was famous for throwing lavish parties at his Yorba Linda home, including one party where Garvey, clad in a Hawaiian shirt and khakis, was shown in photos mingling with clients.

In addition to the mortgage business that Garvey promoted, Favata ran a scam investment arm that promised 30% to 60% returns to clients who refinanced their homes and invested the cash. Favata used the money from the scam’s new investors to pay monthly returns to clients who had invested earlier, a structure known as a Ponzi scheme.

Prosecutors said Favata stole $32 million before the business collapsed. The Securities and Exchange Commission never accused Garvey of wrongdoing, but said that Favata had used his fame to give the scam “an aura of legitimacy.”

Before Favata’s sentencing, Garvey wrote to U.S. District Judge Andrew Guilford to ask for mercy. Favata was a “fundamentally decent and caring person at his core who made a tremendous mistake,” Garvey wrote, and added that he was grateful to “go to bat” for his friend.

Favata pleaded guilty to a federal fraud charge and was sentenced to five years in prison, which Garvey described as a “sad day.”

Garvey also joined a long line of creditors trying to claw back some money from the insolvent company in bankruptcy court, filing a claim for $675,832 that he said he was owed.

The trustee sorting through National Consumer Mortgage’s bankruptcy saw it differently, and tried to reclaim $157,000 that Garvey had already received. The company’s trustee said that at least $28,000 had been transferred to Garvey in the three months before the company collapsed.

Garvey did not admit to any wrongdoing. He agreed in 2010 to pay back $20,000 to the trustees in monthly installments of $400.

Pitchman for weight-loss drugs and reverse-mortgages

In 1999 and 2000, Garvey worked as a spokesman for a weight-loss supplement called Enforma, which contained ephedra, an amphetamine-like herb that was later banned.

In a 30-minute infomercial, Garvey told viewers they could lose weight while eating high-calorie foods like barbecued ribs and buttered biscuits by taking two pills called the “Fat Trapper” and “Exercise in a Bottle.”

The Federal Trade Commission sued Garvey in 2002, saying he made “flagrantly wrong” claims about the drugs. In a decision critical for celebrity spokespeople, a federal court ruled that Garvey was not liable for the false claims in the ads.

More recently, Garvey has returned to the mortgage industry to boost an Orange County company that sells reverse mortgages and educates real estate agents on how to sell them to their clients. The reverse-mortgage industry, which is focused exclusively on older Americans, has long relied on aging celebrity pitchmen, including actors Tom Selleck and Henry Winkler.

A decade ago, Garvey also sold some of his most financially prized awards at auction, including his 1981 Dodgers World Series trophy (sold for $39,381.60) and his 1974 Most Valuable Player award (sold for $68,481.60).

He told the Palm Springs Desert-Sun that financial problems weren’t the reason for the sale. After surviving a brush with prostate cancer, he said, he wanted to raise money to spread awareness of the disease.

[ad_2]

Source link