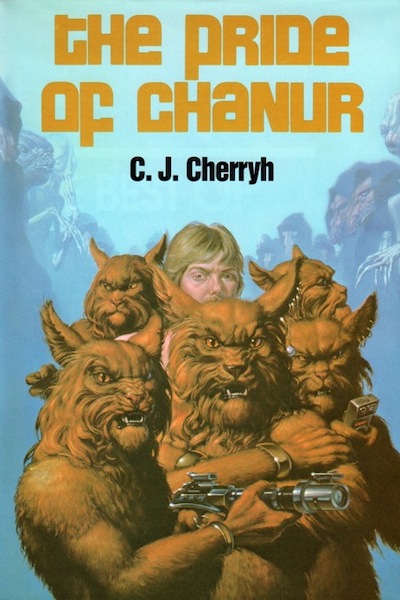

I’ve been meaning to discuss some of C.J. Cherryh’s novels in the QUILTBAG+ Speculative Classics series, but I was unsure where to start. Then I realized that her Chanur space opera series was included in my pre-2010 neopronouns in SFF list, and I’d eventually like to review all titles on said list. Even if the pronouns turn out to be a minor part—which sometimes happens with these older works—it is still likely for these novels to contain some sort of interesting approach to gender.

This was indeed what I found, in this particular case. The first volume of the series, The Pride of Chanur (1981) does include neopronouns: specifically the stsho, one of the non-human species in the narrative, use the pronoun gtst. “The stsho proffered delicacies and tea, bowed, folded up gtst stalklike limbs—he, she, or even it, hardly applied with stsho—and seated gtst-self in gtst bowlchair, a cushioned indentation in the office floor.” (p. 13)

The stsho also have three sexes: “Methodical to a fault, the stsho, tedious and full of endless subtle meanings in their pastel ornament and the tattooings on their pearly hides. They were another hairless species—stalk-thin, tri-sexed and hanilike only by the wildest stretch of the imagination, if eyes, nose, and mouth in biologically convenient order was similarity.”(p. 12)

As we might already see here, the stsho are vaguely queer-coded, but they also play little part in the plot of this novel; this might change in the sequels. Instead, the story centers on the hani, fur-covered sentient beings most comparable to lions. (The “pride” in the title thus becomes ambiguous—is it about the emotion, or the group of lions? Most likely both.)

Pyanfar Chanur, captain of the spaceship The Pride of Chanur, faces a series of difficult decisions after a strange hairless creature runs onto her docked ship on a busy space station. Pyanfar and her crew soon realize the creature is sentient and capable of speech, but as they try their best to communicate, it turns out that this male of a so-far unknown species has escaped from the kif—another member species of the trade alliance called the Compact, alongside the hani. Pyanfar refuses to surrender the so-called “human” to the kif after the human claims to have been mistreated by them. An enormous mess ensues, with the fate of the Compact itself on the line…while Pyanfar also faces danger on a personal level, as the Chanur are embroiled in a battle over family succession.

Cherryh explores multiple aspects of this setup in detail. Various plot points emerge from the communication difficulties not only between the lost human and the hani, but also between different Compact member species. I especially liked that the setting featured automated translation, but it still needed initial data to be fed to it to approximate even a rough translation, which required effort from the characters. It was also interesting to see that there was also a trade pidgin between some—but not all—of the Compact species despite said automation. But for the purposes of this column, it’s probably more relevant to look at how Cherryh tackles gender, sex, and biological determinism in the novel.

It is only the women of the hani who travel in space. All ships are gender-segregated. The men are considered too erratic to go to space and behave themselves there; and indeed, they do spend a lot of their time physically fighting each other for dominance back on their home planet. But—and here I’ll have to discuss some developments in later chapters, though I won’t spoil the overarching plot—this strict biological determinism is undermined by Pyanfar Chanur herself, who finds herself wondering if said differences in gender roles are innate, or due to upbringing.

I don’t know if I should call this a genderswap when there is so much variation on our own Earth in these kinds of roles. In one of my own cultures, it was traditionally the women who traded and made a living, though for a different reason than the hani: the men were busy with their religious duties. Maybe I could say that the hani are a genderswap of many Anglo-Western cultures, though this would also be an oversimplification: Cherryh crafts her world with her trademark sense for nuance and detail here as well as in her other novels. This is the type of space opera where you find out exactly how docking clamps work, and that also extends to social aspects beyond the technological, like gender roles.

Humans still seem to be humans, and their own ideas about gender affects how the hani who come into contact with them proceed to think about their own gender. This is done in a surprisingly gentle way, with Tully the escaped human modeling a kind of masculinity that is as far from toxic as possible, while the narrative also affords him room for vulnerability as someone far from home, an outsider cut off from anything familiar.

There’s something intriguing about the premise of a crew that’s single-gender for reasons of chastity (and again, I’ll need to go into a bit more plot detail to discuss this point). When speculative works include this arrangement as part of the plot, I tend to expect the intent to be subverted by showing that same-sex attraction exists. This is what I expected here, especially in a work which already had neopronouns and an interesting approach to gender. But what happened in The Pride of Chanur was altogether different: the presumably-straight man ends up on a ship of straight women, and they all decide to be professional about it and not act on any potential desires. (Despite the difference in species, the question does present itself—at one point, the captain worries that one of her crewmembers might start a liaison with the human.)

I found this approach refreshing and it poked against my own preconceptions of what a gender-conscious science fiction book should look like, alongside the portrayal of human masculinity. Is the reader expecting Dudebro—because he is a dudebro, not just a man, but a specific kind of man—to do something catastrophically awful? Most likely, yes. The entire crew certainly expects him to do just that. Captain Pyanfar herself considers this repeatedly, treating the human with caution, and only allowing him increasing leeway by small increments. Does the reader expect some of the women crewmembers to be attracted to each other? Maybe not in 1981 (though I’m not sure about that—the trope existed at that point), but today, definitely so. This doesn’t happen either, and yet gendered aspects of the setting have been destabilized in a way that is deeply feminist. This is much less apparent on the surface than the three-sexed aliens with their neopronouns, who we sadly don’t see much of in this novel, but is more impactful structurally. It also enables Pyanfar to examine her own biases, and act on her realizations.

A final note: when I showed the first draft of this review to my spouse R.B. Lemberg, they asked me if I knew whether Cherryh was reacting to Larry Niven’s Kzin stories, which feature catlike aliens who are extremely male-dominated. I’m honestly not sure if this is the case—I looked and I’ve only found fans comparing these works, but no discussion or statement directly from the author.

I’m very much looking forward to seeing where Cherryh takes the series next—the following three books form a trilogy, and I’m hoping to cover them in my column as well. They will be interspersed with standalone works by other authors—for next time I have a novel queued up that won both the Hugo and Nebula awards. I’m also considering covering more Cherryh after I’m finished with the Chanur books: do you have any particular favorites?