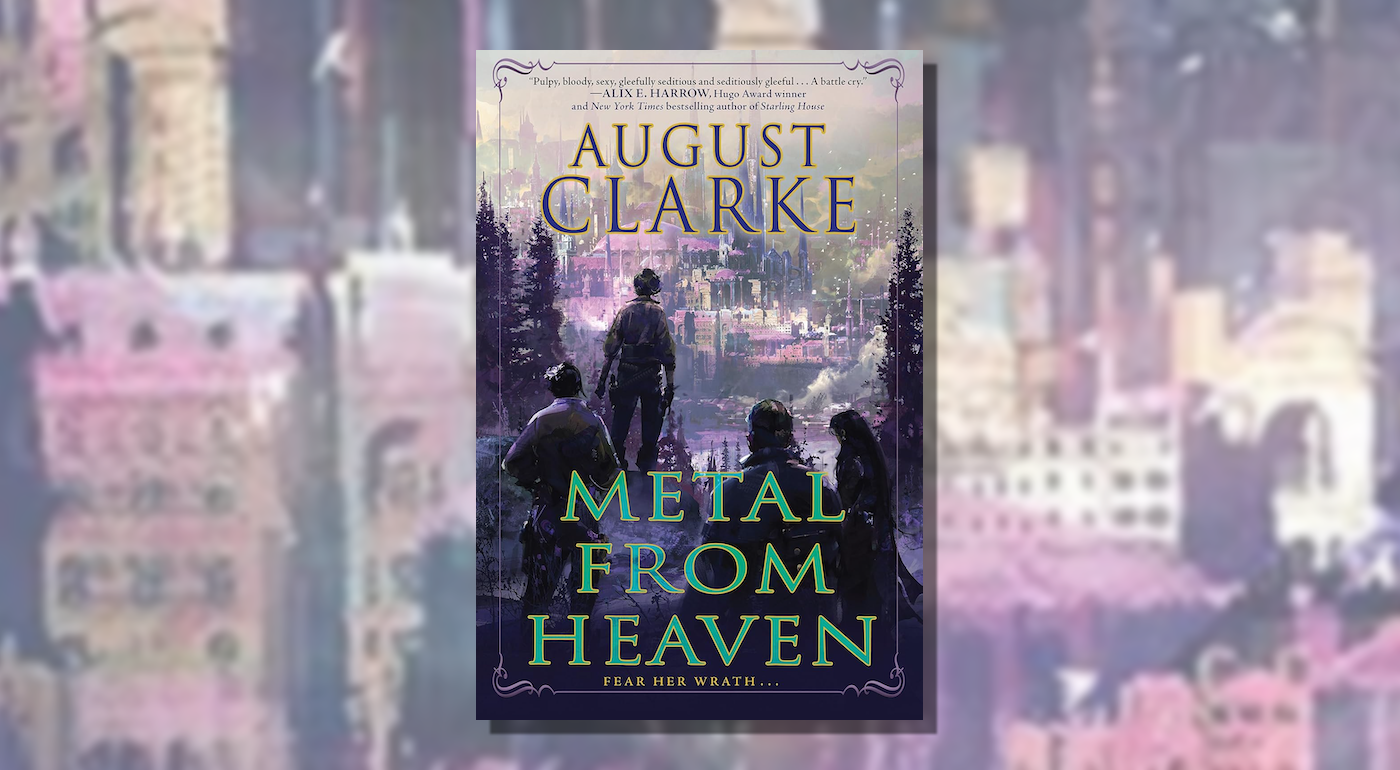

We’re thrilled to share a bonus excerpt from august clarke’s Metal from Heaven, a caustic, dizzying eco-fantasy that addresses labor politics, corporate greed, and the relentless grind of capitalism, while also embodying a visceral lesbian revenge quest against the people and institutions who control and oppress the helpless—publishing with Erewhon Books on October 22nd. If you missed the first excerpt, you can find it here!

He who controls ichorite controls the world.

A malleable metal more durable than steel, ichorite is a toxic natural resource fueling national growth, and ambitious industrialist Yann Chauncey helms production of this miraculous ore. Working his foundry is an underclass of destitute workers, struggling to get better wages and proper medical treatment for those exposed to ichorite’s debilitating effects since birth.

One of those luster-touched victims, the child worker Marney Honeycutt, is picketing with her family and best friend when a bloody tragedy unfolds. Chauncey’s strikebreakers open fire.

Only Marney survives.

A decade later, as Yann Chauncey searches for a suitable political marriage for his ward, Marney sees the perfect opportunity for revenge. With the help of radical bandits and their stolen wealth, she must masquerade as an aristocrat to win over the calculating Gossamer Chauncey and kill the man who slaughtered her family and friends. But she is not the only suitor after Lady Gossamer’s hand, leading her to play twisted elitist games of intrigue. And Marney’s luster-touched connection to the mysterious resource and its foundry might put her in grave danger—or save her from it.

An introduction to the excerpt from the author:

Marney Honeycutt has spent years in the Choir, a family of rebels, revolutionaries, and the repressed living in the Fingerbluffs; there, they have kept a pretense that the nobility who used to rule it yet lives, though the ruse may be up any day. With her friends, Marney has become a notable bandit, the Whip Spider, whose touch melts the magic metal ichorite and whose gang gleefully robs from the wealthy.

Aboard a riverboat, heist nearly complete, Marney runs into a problem in the shape of a girl with a knife, as elsewhere, the Choir must decide it’s collective future…

She was a tall, lean girl. Hair blacker than the shadows surrounding swayed around her hip bones and was slicked back from a sharp face, all bone and diagonal angles save for her watery downturned eyes, long-lashed and burning, and her full painted lips twisted in a horrible smile, or grimace, or leer, I didn’t know. I watched her move her lips soundlessly. She walked like she was Veltuni but wore no lip ring. She held a keen clip-point knife. The girl didn’t blink. She looked like she might cry. She toed off her delicate high-heeled shoes, stood barefoot on the luster-splattered floor, widened her stance. I saw the tension in her thighs and core and shoulders through the dress, saw it release. She pounced knife-first.

I threw my body to the side but the knife clipped my collar. Bright slippery pain flowered under the bone. She cut forward again, I stepped back, I closed my hand and found my knife inside it. Behind my eyes pink bubbled. I slashed back, she drove a cut upwards, would’ve knocked my knife from my hand if its metal hadn’t seeped into my skin. This girl was—better. She moved with a viciousness just past efficiency, a studied meanness. Sport dueler, though this—she slashed my upper arm, the cut flowed thickly—was not the restraint and acclaimed elegance of an aristocratic knife duel, not that I had any right to judge an aristocratic knife duel. She was a cat and I was a finch whose wing she’d already torn. Lots of light cuts to watch me bleed because she could. And she could. I chanted in my head, kneaded the ichorite pools underfoot into wires into snares to trip her, but she tore through them like they were nothing before they solidified. The ichorite strings snapped and drooped and became solid again. She seized a fistful of my jacket, fit her knife under my chin, and leaned me over the cargo bay’s edge, balls of my feet on the floor, heels in open air above the drop to the whirling catfish.

“You wretch,” she purred through her teeth. “You slime. You’re a carnival barker. You’re a road magician. You’re not a devil, you lack the dignity demanded by a symbol so rich. You’re nothing and nobody. How dare you frighten that girl like that? How dare you interrupt us?”

I panted. I didn’t dare move.

“You are a stain on our age. You are a blemish on progress.” She leaned over me. Her hair swayed against my slit jacket. Strands clung to where I bled. I felt her breath on my cheek, the sweet liquor on her snarl. Her eyes were enormous. I saw my horror mirrored across the little pink veins there. “You little freak. You little sadist. The look on that server’s face. The disruption you’ve caused, the disrespect you’ve showed my staff, is repulsive. You don’t deserve the air in your lungs. You don’t deserve the blood in your body.”

Buy the Book

Metal from Heaven

I willed the ichorite off the ground and felt my vision flicker. The world bruised. It bubbled, I saw the metal effervescing in my periphery, but I couldn’t will it to shape. Yann Chauncey lived. I could not die while Industry lived. That man didn’t even know where my father was. I couldn’t die. I looked into the eyes of this girl, her liquid black eyes, and did not know how to kill her.

“Drop the knife,” said Sisphe thu Ecapa, her gun nestled at the nape of the stranger’s neck. “This is my little freak.”

The stranger’s face rippled. She looked furious, then exasperated, then fell into a sullen humor. Her eyebrows danced under her fringe. Her lip twitched. She threw down the knife. It thwunked into the scuffed plank floor. I breathed in sharply. She released me.

I felt gravity win.

The sky flew up in pink and orange slashes, and the Flip River slapped me, grabbed me with a thousand flapping catfish mouths. My head slipped under. The writhing fish bodies covered the boat above me. They whirred around my body, slimy and muscular, and I clawed at the nothing between their bodies. I saw long algae like hair and a limp, drifting hand.

Then fists closed around my upper arms and pulled me upright. I gasped, the evening burned against the lining of my throat and I spat up murky water, and collapsed against Brandegor the Rancid, who clapped me firmly between the shoulder blades so hard that something knocked loose. I shivered. I coughed up a laugh, I laughed so hard I cried, I sobbed into Brandegor’s shoulder. She mussed my curls. The orange darkness behind my eyelids spasmed with luster luster luster.

* * *

Sometime later we triumphed around the Fingerbluffs. We leaned off our lurchers and gave luxurious silks and fine jewels to everyone who gathered to watch us pass, and the crooked teeth they showed us were beautiful, and the air was perfumed with marmalade and tobacco flowers, and Harlow and Sisphe and I reclined on the cliffs like natural princes, eating fruit and sunning ourselves, drenched with scrapes and bruises. We looked at the place where Candor should be lying and I told Sisphe and Harlow about you. That time you stole raspberries for us. The day I made that ring for you. Pinched it from conveyor belt scraps and kneaded it for your littlest finger. I contemplated and then forbade the contemplation of whether your body wore that ring in whatever unmarked grave Chauncey’s goons had planted you in. Was your body dissolved into my family’s body? Had you fused with Edna and Poesy and the boys who chased you when you were smaller? Were you dissolved into flora? Had you been transformed into endless flying things? I thought about cicadas, underfoot for ages until maturity comes. Screaming flight.

It’s easy when it’s hazy to imagine that there is something moving underneath these rocks. Moving gently, breathing. Something deep asleep. It’s easy to imagine a watchful slumber. My old religion has its merits. I rolled my cheek to the side, pressed it flush against the basalt and the forgetme-not sprays, and listened to a heartbeat I could not explain to my friends. My tongue itched. I scraped it with my teeth. I was eager again to eat the guts of Industry Chauncey. I gnashed my molars and yearned.

Uthste came and found me. She looked older, her eyebrows were dusted with gray. She stood over us on the rocks, where we passed a bottle between us, some rosy fizzy tonic edged with coca leaves, and her shadow interrupted our murmuring. The sun behind her shaved head looked crownlike. She frowned gently. Her boots glistened by my ear. She said, “It’s the end. Marney. Come along with me, please. Amon’s asked for you.”

“Just Marney?” Sisphe put her elbows under her.

“Never just Marney,” said Harlow, dragging a comb through her glossy black hair.

Uthste nodded curtly. “Marney by name. Come as you’d like. Be quick.”

I found my feet. Harlow followed me, and we both took one of Sisphe’s clever faux-limp hands, hauled her upright, whisked her off to Loveday Mansion. I felt small following Uthste. I wondered if she knew what she symbolized to me, herself and Valor and Brandegor, my saviors and bandit-makers. The thought of telling her seemed a repulsive imposition. I reckon she’d know when I showed her. I’d have to demonstrate it in deed.

The four of us gathered in the ballroom. Settees and wingback armchairs had been dragged in and arranged around the broad room’s perimeter, and Choir-goers, not full quorum but more than I usually saw in one place, flocked among the velvet furniture in corduroy and rough leather, features hard against the plushness. Younger kids lay on animal-pelt rugs and pulled the tufts of fur. A boy near me braided down a dead bear’s back. He looked eight, maybe. Truly eight. He’d never seen hard labor and it kept him babyish. The abundance of bandits humbled me. I felt grateful and young, but tired.

Uthste went and sat on the floor in front of Brandegor’s chair, leaned back against her shin. Valor perched on the chair’s arm, one of Brandegor’s big arms around her waist. I scarcely knew what to do with myself. I looked back to Harlow and Sisphe, ached for Candor, then Sisphe turned my chin with her knuckles and pointed my attention at the room’s far end. Amon sat on the floor with letters and telegrams and newspaper clippings fanned in front of him. Behind him, the Veltuni ancestral congress’s cast hands kneaded and stretched. I leaned my cheek against Sisphe’s hand, felt an old flicker of something I couldn’t entertain, then crossed the cream-and-amber room and knelt beside Amon.

Amon smiled but did not look at me. He moved his hands, I moved mine back, an acknowledgement of our mutual faith.

Amon said, to the room itself, “Thank you, assembly. I’ll be brief. Our masquerade has always been finite. Twenty years in glorious harmony will imminently meet its abrupt end. I believe this because the heir to Loveday Mansion is of age, and has been summoned to Yann Industry Chauncey’s estate. His ward has a debutante showing. The Loveday heir has been invited by three separate parties, the Montrose barony, the Glitslough barony, and the Chauncey family itself. If we decline, our only option, they will come here. They will send their emissaries. Lately, we had plans for this. But our sweet girl Candor is dead.

“The barons of Ignavia alone supposedly own land. Before my friends killed him, Horace Veracity Loveday claimed to own this land. All the people who worked this land rented their homes from him, owed him the fruits of their labor, and the tools with which it was performed, and were subjected to his whim as law. The Baron’s Senate is firm about land ownership remaining in their few fists, but the Baron’s Senate is poor, and the money is in Industry Chauncey’s industry. Chauncey can’t own land. All ichorite refinement centers are clustered around IC, as Baron Ramtha has been enormously lenient with allowing Chauncey’s growth, but Chauncey wants to expand his enterprise. They need land and lots of it, land for mining, land for processing plants, land for the workers who labor in those pits to sleep on.

“Chauncey is asking after us because he wants a baron-class spouse for his ward. He wants this because he wants to mine here, or thinks he can. We can refuse. We can put it off. But the emissaries to be sent won’t only ask after the Loveday heir, they’ll scout the Fingerbluffs for mining. The blurring between the capitalists and the barons is already happening. This marriage, whatever it might be, will mean that Chauncey will come to conquer us. He funds the Enforcer Corps. They will come with force and we will battle until we are dead, and then our home will be maimed and stripped for parts.”

Gray faces around the room. Nobody blinked. Murmurs rumbled but I caught no words. I put my hands on the floor. I looked at my hands. My fingers were blurring.

“We prepare for the war,” said Brandegor. Valor beside her looked stricken but sure. They’d go down blazing.

“We leave. Be reasonable,” said a bandit called Alcstei zel Prisis.

Alcstei’s man, whose name I did not know, said, “The Choir can claim a new home. This place has served us for twenty good years, but the Choir must be preserved. We find a new stronghold.”

“We serve this place. Not the reverse. Have pride,” snapped a bandit called Aturmica thu Artumica Tanner. “Do you imagine we will take with us the community who has defended us and nurtured us for decades? Beg the displacement of thousands upon thousands? Tell them to carry with them their histories on their backs and be dispossessed of all else, we’ve surrendered their home to the slaughterhouse? Or do you suppose we abandon them?”

“I was born on the Bluffs,” said Valor. “Here’s where I’ll die.”

“We will not suffer the indignity of surrender. We won’t show belly, we won’t scurry under some rock. Be righteous, Alcstei.” Brangedor pulled attention like gravity. She strained against her clothes, against her skin. She held Valor’s waist and Utshte’s shoulder to keep herself seated. I thought she’d kill Alcstei with her hands. “We lost five this month. Five of us. Young Thomas Fortitude shot off the roof of a train, his body caught and brought home by his boys, buried by hand in the fruit grove. Cristhia’s twins, gone. Dash Mercer, dangling up in Geistmouth. Wyatt Piety Stytt, dangling down in the Achrum prairies. We commit ourselves to death when we mark our names across our breasts. We will die for this. I am the last bull rider of Mors Hall. I will die for this place.”

Alcstei’s man stood up.

“Be fierce and proud for our Hereafter. To die for tomorrow is to die for our children’s rich harvest,” Harlow said.

“You don’t have children,” said Alcstei’s man. “We do.”

I stood up. My hands shook, I rooted them in my hair. My ribs beat against my jacket. I spread my elbows, looked across the room at nobody in particular, at everybody, at Sisphe. She gave me a sharp nod. Her eyes flashed. I looked down at the papers fanned around Amon, the array of blue and cream off-whites. I couldn’t read the sinuous handwriting. The ink on the pages still looked wet. “The Loveday heir should say yes. I’ll be the Loveday heir. I’m not Stellarine but I can fake it. I studied to be Candor’s valet.”

Amon looked up at me. He looked relieved. At last, I’d said it.

“Pardon,” I said. I looked to my peers and fixed my tone. “Gentle Choir. I propose that I go feign being Loveday heir.”

A bandit whose name I didn’t know said, “Would the charade be worth it? It pushes back war only so far.”

“It’s worth it because I’m gonna kill Yann Industry Chauncey,” I said.

“That’s true,” said Brandegor the Rancid. “She is gonna kill Yann Industry Chauncey.”

“If Marney takes up the role,” Sisphe said, vibrating with such glee that I thought her hairpins might fall, “and I accompanied her as her secretary or her valet, think of the recon! I could squirrel away as many documents as I can. Muddle things up for them. If we’re to have a war, killing Chauncey is a triumphant first blow. Let’s not be passive. Let’s not wait like lambs.”

“When Marney takes up the role,” said Harlow, “we’ll have bought ourselves another month or two to strategize. We’ll know what their plans are, we could maybe even shape them, arrange the conditions of our discovery on our own terms. Be keen and ruthless against them, having studied their intentions and so on. Let her take on Candor’s work. Let her be our girl’s remembrance.”

“Yes, and it’d be funny,” said Magnanimity, the oldest bandit in the room, who’d served the Choir for forty-seven years, and been present for Horace Veracity Loveday’s execution. She rolled her wrist, clanged her bangles together, and smiled at me. “That’s as good a reason as any.”

“Marney deserves to kill Chauncey,” said Uthste. “And we deserve him dead for the threat he poses.”

Magnanimity clapped her hands. “Those who want to flee, flee. Take a civilian’s portion of treasure and be gone from our graces. Show of hands. Marney as Loveday heir to kill Yann Industry Chauncey?” Hands drifted up. The ancestral congress stretched their fingers behind my head. It felt like dusk bleed when I was small, all the floating palms. Such pride I had for the whole world. Such pride I had in my own survival. Such love for the Fingerbluffs, for the Choir, for my families, for you. My blood was thick and vibrant. Cut me and find grenadine. Cut me and find white hot light.

Excerpted from Metal from Heaven, copyright © 2024 by august clarke.