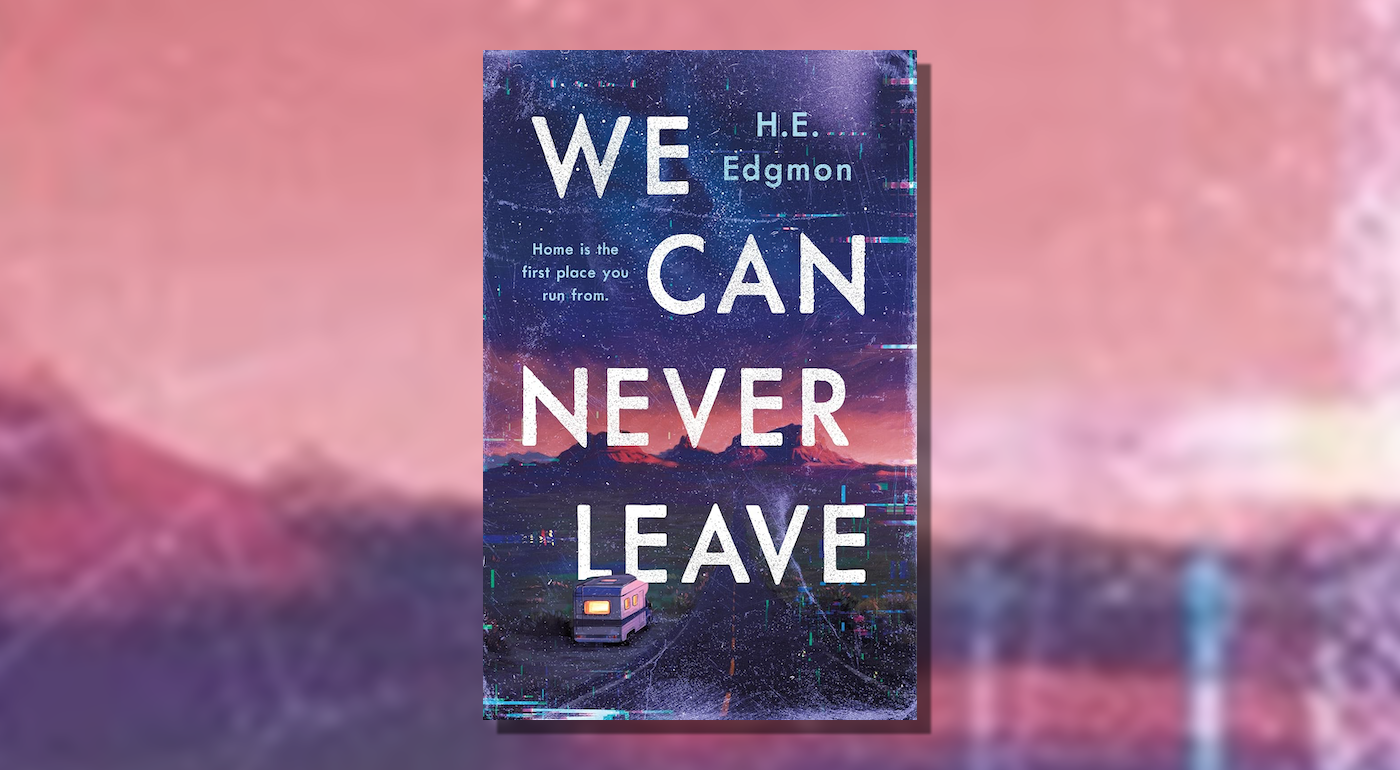

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from H.E. Edgmon’s We Can Never Leave, a queer young adult contemporary fantasy about what it means to belong—publishing with Wednesday Books on June 10th.

Every day, all across the world, inhuman creatures are waking up with no memory of who they are or where they came from–and the Caravan exists to help them. The traveling community is made up of these very creatures and their families who’ve acclimated to this new existence by finding refuge in each other. That is, until the morning five teenage travelers wake to find their community has disappeared overnight.

Those left: a half-human who only just ran back to the Caravan with their tail between their legs, two brothers–one who can’t seem to stay out of trouble and the other who’s never been brave enough to get in it, a venomous girl with blood on her hands and a heart of gold, and the Caravan’s newest addition, a disquieting shadow in the shape of a boy. They’ll have to work together to figure out what happened the night of the disappearance, but each one of the forsaken five is white-knuckling their own secrets. And with each truth forced to light, it becomes clear this isn’t really about what happened to their people–it’s about what happened to them.

The night the unthinkable happened, Bird woke to the sound of fevered laughter and their own desperate gasps for air. As their dreams brushed against reality, they could’ve sworn they were choking, their own wild heart trying to clamber up their throat and into their mouth.

As dreams do, the sensation faded, and Bird was left with only the laughter outside their bedroom window and a pit in their stomach. They threw away the age-softened blanket and tugged their legs to their chest, pressing their sweat-damp forehead to their knees in a bid to recalibrate to the waking world and their body. Cool air, heavy with a stale residue of incense and the all-natural deodorant that clung to their soft palate, nipped at their ears and stamped gooseflesh across their skin. Fingers, toes, thick with pins and needles. Heartbeat, there you are, you, drumming beneath their temples. Bird had never been a stranger to nightmares, though these unsettling dreams had become increasingly unrelenting in recent months.

Perhaps that was no surprise, considering how unsettling their everyday had become in tandem.

In fact, for that very reason, bedroom window was hardly an apt description for the divide between their bed and the revelers outside. When Bird finally lifted their head, it was to squint at the tiny panel of cloudy glass embedded at the rear of their mother’s camper. Beneath it, their twin-sized cot with its inch-thick foam mattress had been propped open— the same cot Bird had slept in for most of their childhood, and a place they’d once planned to never sleep again. At least this time they’d been generously allowed something resembling a wall—a faded old bedsheet strung up from the ceiling to act as a curtain between their corner and the rest of the makeshift home. If Bird didn’t know better, they’d think its threadbare state a personal slight—the pettiest of little revenges for daring to leave in the first place. But the fact that they could still see every twinkling fairy light and abandoned candle on the other side wouldn’t have been flagged as a problem to their mother, even if she had noticed.

They pressed their knuckles into their eyes as if to rub away the dogged tendrils of sleep or the steadily encroaching headache. When someone gave a delirious shriek from the campground and sent a spike of pain through Bird’s eardrums and into their limbic system, they accepted defeat. They fumbled in the dark for their phone before their fingers tightened around cool metal and tugged it free of its charger. Air hissed through their teeth at the burning light of the home screen, eyes struggling to adjust.

11:43 p.m. Nearly midnight, and the lunar festivities refused to be quelled. Bird couldn’t even remember if it was a new moon or a full moon they were dancing under. In either case, it would do no good to try and convince anyone to keep the volume down. If they so much as asked, Bird would only be teased for being a stick-in-the-mud.

Resentment, like acrid smoke, lapped at the inside of their mouth and tasted their eyeteeth. Returning to their role as the Caravan’s insipid court jester was as unwanted as returning to their sad old cot.

Buy the Book

We Can Never Leave

With a groan, they threw back the curtain and stomped into the dark of the camper. Of course they were alone, their mother’s nest of a hammock abandoned over the pull-out kitchen table, fringed blanket edges teasing the Formica. Holly Stieber would be nowhere else but at the center of whatever was happening outside.

More familiar resentment, an old bruise that might’ve healed if Bird had ever learned to stop pressing on it.

The outside air was chilled, autumnal and sharp, and Bird doubled back for shoes and a mantle the first time they ventured into it. On the second attempt, their sandals met brown grass, their fingers twisting in the woven tapestry draped over their shoulders, and Bird—who was being very brave— ventured toward the smell of the Caravan’s hopes and dreams going up in flames.

It was, in fact, a new moon being celebrated. New moons, new beginnings. Marking a cosmic rebirth, they were nights when the universe begged all creatures to make their desires known. And just by doing so, they might wish them into existence.

The ritual happening at the campground was one Bird had grown up watching every month for nearly their entire life. Members of the Caravan scrawled their wishes on scraps of paper and threw them into the flames, their smoke signals decorating the sky like prayers wafting to the ears of a nameless, omniscient god. And all night, they danced, barefoot and drunk and brimming with hope for what was sure to come in the aftermath of the night’s magic.

Nothing ever came, and there was nothing listening. Bird had figured that out a long time ago.

But that is what a stick-in-the-mud would say.

No one noticed when Bird’s cloaked shadow joined the edges of the party, too busy enjoying themselves. That was for the best. Bird didn’t need—or want, really—to be seen here; they were only here to watch. Golden eyes flicking through flame-shrouded bodies, they searched the crowd until they found their mother.

The sight of her made Bird’s stomach gurgle, their hands curling even tighter into the tapestry weave. Holly was practically nude, unsurprisingly, and her bare skin was lathered in oils and powders made of dried, crushed herbs. Her hips rolled and her head swayed, both with such frantic conviction that it made her levitate, looking less like a dance and more like a situation that warranted an ambulance. If the Caravan were made up of the sort of people who ever called an ambulance.

Not far behind Holly were her parents, Bird’s grandparents, Basil and Cassandra. The couple sat on the steps of their own RV, watching the gathered crowd. Elders in the Caravan, Bird’s grandparents had been around nearly since the community’s inception. Neither had been born into it—instead, like so many of their people, they’d been found. Now they continued the work that had brought them safety and community, traveling the country to find others who needed them. Others who were… different.

Bird’s eyes fluttered over their grandmother’s forehead, to the curled snakes making a crown around her skull. As they watched, another snake head appeared, peeking through the dark coils of her hair—then another, and another. Cassandra whispered something to her husband, her own forked tongue flicking into the air between them. Basil’s wings, soft tawny feathers turned monstrous by a trick of the firelight, twitched behind them, curling his wife closer.

Different, yes.

Not everyone in the Caravan was as easily identifiable as Basil and Cassandra. Holly had inherited pieces of both her parents but—though she did literally levitate—could pass as human when it suited her. It’d certainly suited her when she’d met Bird’s father, a very average and normal human himself. And Bird, for their part, may as well have been 100 percent free-range grass-fed Homo sapiens. At least on the surface.

Their appearance had served them well three years ago, when they’d decided to leave the Caravan, never intending to return. For three years they’d managed to live with their dad in the world of humans, chasing a life they thought they might be able to build there. Of course, they’d failed. In the end, everything fell apart before it had the chance to come together, and Bird was forced to run back home and beg for a place to stay and their inch-thick mattress. Forced to bite their tongue until they tasted copper and accept their mother’s sympathetic grace. It didn’t matter what they looked like. They would never be human. And more, this would always be the firelit hole they’d crawled out of.

Someone had warned them of that, once, before they’d run away. But Bird hadn’t listened to him.

Their eyes searched the crowd for another face, hungrily seeking a familiar set of antlers.

Where are you, Hugo? What wishes are you throwing in the fire tonight?

What would a boy without hope demand of the universe, anyway?

Before they managed to locate the bony branches of their splintered other half ’s brow, Bird’s gaze stuttered on an ominous red glow from within their grandparents’ RV. Their eyes skittered quickly away but doubled back again, locking with the cardinal blood-moon stare that burned even from behind glass.

On the other side of the window, Eamon, a shadow in the shape of a boy, watched them. The newest addition to their Caravan, Eamon had been picked up and collected into the fold only days before Bird’s own return. Like so many who’d come before him, he had no memory of who he was or where he’d come from. The nature of his power was unclear. He was staying with Bird’s grandparents until he’d found his footing.

Or perhaps until he’d killed them all in their sleep. Bird did not get a good feeling from the guy.

Only those red, red eyes and the sharp planes of his face could be made out, illuminated by the glow of the fire between them. Interesting, how his eyes could so closely match the shade of popping ember venturing to warm the bleak October midnight, while the weight of them could feel like ice on Bird’s skin.

For the second time since waking, they felt their throat tighten. The chasm of that stare was too deep to wade into, singing a kind of primal warning that made Bird want to bolt for the camper and bury themself beneath every timeworn scrap of fabric they could find. For someone who seemingly knew nothing, Eamon certainly stared at them as if he knew everything he needed to know. It was as if he could see right through them—a particularly terrifying thought, since no one really knew what he was or wasn’t capable of.

Least of all himself. Or so he said.

He looked at Bird as if he knew everything they kept tucked behind their teeth. As if he knew exactly what dreams had been haunting them, and which ones they would throw into the fire tonight if they dared to throw any at all.

Bird broke his stare, turning away from the window.

If that were the case, Eamon would benefit from keeping his eyes on his own page. The things Bird didn’t say went unspoken for a reason.

Some prayers were better left unanswered.

From We Can Never Leave by H.E. Edgmon. Copyright © 2025 by the author and reprinted with permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.