It was a meeting of two of the most powerful men in Los Angeles — and there was no way Richard Alatorre would lose.

Police Chief Darryl Gates and his command staff had stopped by Alatorre’s office to introduce themselves. Alatorre, newly elected to the City Council, stayed seated, feet on his desk, a friend looking on. Gates offered some pleasantries before Alatorre cut him off — and down — with a question: “Where are the greasers?”

The police chief was flummoxed. Alatorre, already a political force in Eastside and California politics, asked the same question again, letting the last word — an antiquated slur against Mexican Americans — make the top brass squirm.

Gates finally said he didn’t understand the question. The council member replied that the Los Angeles Police Department had no Latinos in its upper ranks, and that Gates could return when he fixed that. Meeting over.

It was classic Alatorre: uncompromising, uncouth and unapologetic in the name of exerting his influence to better Latinos. And effective: Gates eventually conferred with him about how to diversify LAPD management.

“I’m not just one that opens his mouth and meow-meows about a given subject and then moves on to the next topic without ever getting your hands dirty and trying to get something done,” Alatorre told a UCLA historian in 1990, a few years after his encounter with Gates. “No, I try and see it to its end, backroom deals and everything.”

Alatorre died Tuesday morning at his home in Eagle Rock after a long battle with cancer, surrounded by friends, family and former staffers. He was 81.

The son of a Mexican American mother and Mexican immigrant father spent his 28-year political career practicing what he called “change from the inside”: climbing California’s political hierarchies and bringing other Latinos up with him.

In Sacramento as an Assembly member, the gravel-voiced Alatorre pushed through bills on prison reform, bilingual services and farmworker rights. He oversaw a landmark reapportionment in the 1980s that helped Latinos enter the state Legislature in numbers never before seen, doing the same for Los Angeles after joining the City Council.

“A lot of us considered Alatorre to be a vato who made good,” said Jaime Regalado, professor emeritus of political science at Cal State L.A. Alatorre frequently spoke at Regalado’s classes and was more than happy to take questions from students who thought he was a vendido — a sellout.

“But lo and behold, through his reputation in his years, he became the vato for a lot of people,” Regalado concluded.

As he won rights and access for Latinos statewide, Alatorre built an Eastside political machine that drew accolades and criticism. At the end of his career, scandal threatened his legacy as he fended off investigations into alleged corruption and cronyism. Ultimately, his stature remained undiminished among supporters and even some rivals.

Gloria Molina, a onetime acolyte who built a competing Eastside machine in the 1980s and ’90s and once described Alatorre as a “bully” to The Times, gifted Alatorre a commemorative scroll at an L.A. County Board of Supervisors meeting just before he left public office in 1999.

“I’m glad that the wheeling and dealing will be gone,” said the then-supervisor, who died last year. “But at the same time, there’s a lot of things I think we’re going to miss. Richard offered the Latino community political power that it never had.”

Born in 1943 in Boyle Heights and raised in East Los Angeles, Alatorre grew up in an era when Mexican Americans were joining the middle class but found themselves politically ignored. He remembered his father, Jose, a stove repairman who instilled in his son and daughter the importance of education, bemoaning the gerrymandering that kept Latinos from electing more of their own.

On a rainy night in 1960, the family’s outlook on politics changed.

The Alatorres joined 20,000 people at East Los Angeles College to hear John F. Kennedy speak, a week before election day. Richard wanted to leave because of the terrible weather, but his father insisted they stay and witness history.

Kennedy “seemed to be the first presidential candidate reaching into my community and asking for our help,” Alatorre told The Times in 1989. “That represented hope to me.”

He volunteered for the Kennedy campaign as well as that of Leopoldo Sanchez, who became the first Latino judge elected in California. Alatorre became senior class president at Garfield High, moonlighting as a bill collector for a jewelry store before enrolling at Cal State L.A. There, he found a political science class too hard and his classmates too smart, so he told his father he was going to drop out.

Jose said that would create a self-defeating pattern and urged him to reconsider.

Alatorre graduated from Cal State L.A., earned a master’s degree from USC and became a staffer for Eastside Assemblymember Walter Karabian. He headed Latino voter outreach for Tom Bradley’s failed 1968 mayoral run, taught civics classes to inmates at Terminal Island and served as Western regional director for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. As his star rose in mainstream politics, Alatorre maintained his dedication to the Eastside grassroots.

When protesters were jailed and held on $100,000 bail during the 1968 Chicano Blowouts, Alatorre used his connections with the Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy presidential campaigns to raise $300,000. He convinced a judge to reduce the protesters’ bail to $15,000, then went to bail bondsmen he knew to cut a deal. He did the same during the 1970 Chicano Moratorium, which he left just before it turned into a deadly melee.

The following year, Alatorre ran for an Eastside Assembly seat in a special election and seemed headed for an easy victory. But in one of the biggest upsets in L.A. County history, Alatorre finished second to Republican Bill Brophy after a third-party candidate, Chicano activist and journalist Raul Ruiz, siphoned off votes.

Six months later, Alatorre easily beat Brophy in a rematch. He never lost a race again.

The rookie Assembly member initially found himself on the wrong side of Sacramento’s ruling class, clashing with Assembly Speakers David Roberti and Leo McCarthy, San Fernando Valley Assemblymember Howard Berman and Gov. Jerry Brown. Alatorre was nevertheless able to distinguish himself fast with his bare-knuckle style.

When the dean of UC Berkeley School of Law came before a subcommittee chaired by Alatorre to ask for more money, Alatorre told him the school needed to institute affirmative action first. When UC Irvine asked for money to build a medical center, Alatorre made his support contingent on opening health clinics in Santa Ana and setting aside 25% of its enrollment for Black and Latino students.

He was a co-founder of what today is known as the California Latino Legislative Caucus, originally numbering just five members. Alatorre also authored a pair of bills — one mandating bilingual services in communities that needed them, another allowing farmworkers to collectively bargain — that were the first of their kind in the nation. He rose in Sacramento with the support and advice of Willie Brown, a Black Assembly member from San Francisco who proved a kindred spirit.

“He loves clothes and I love clothes,” Alatorre said in his UCLA oral history. “He likes nice things, I like nice things. And we’re the two foulmouthed legislators.”

When Brown became Assembly speaker in 1981, he asked Alatorre to head the committee tasked to redraw the boundaries for state legislative districts.

Alatorre’s job was to ensure that Democrats kept their majority in Sacramento. But he also remembered his dad’s long-ago lament that Latinos didn’t have enough political representation. With the help of computer programs and the input of activists who testified at public hearings, he spread Latino voters over many districts instead of amassing them in a few, anticipating a future in which California’s Latino population would be dramatically bigger.

“It was a critical moment in Latino political history,” said Fernando Guerra, director for the Center for the Study of Los Angeles at Loyola Marymount University. As a graduate student at the University of Michigan in the 1980s, he heard Alatorre speak. “Richard talked about how what he had accomplished in California was doable anywhere.”

Back in his Eastside base, Alatorre was creating a political machine with his friend Art Torres. Alatorre beat a longtime incumbent for a state Senate seat in 1982, the same year two allies won newly realigned congressional seats. But one governing board eluded Alatorre and Torres: the L.A. City Council, where a Latino hadn’t served since Edward Roybal left for Congress in 1963. Standing in their way was longtime Eastside incumbent Art Snyder, who had survived repeated recall attempts and insurgent candidates.

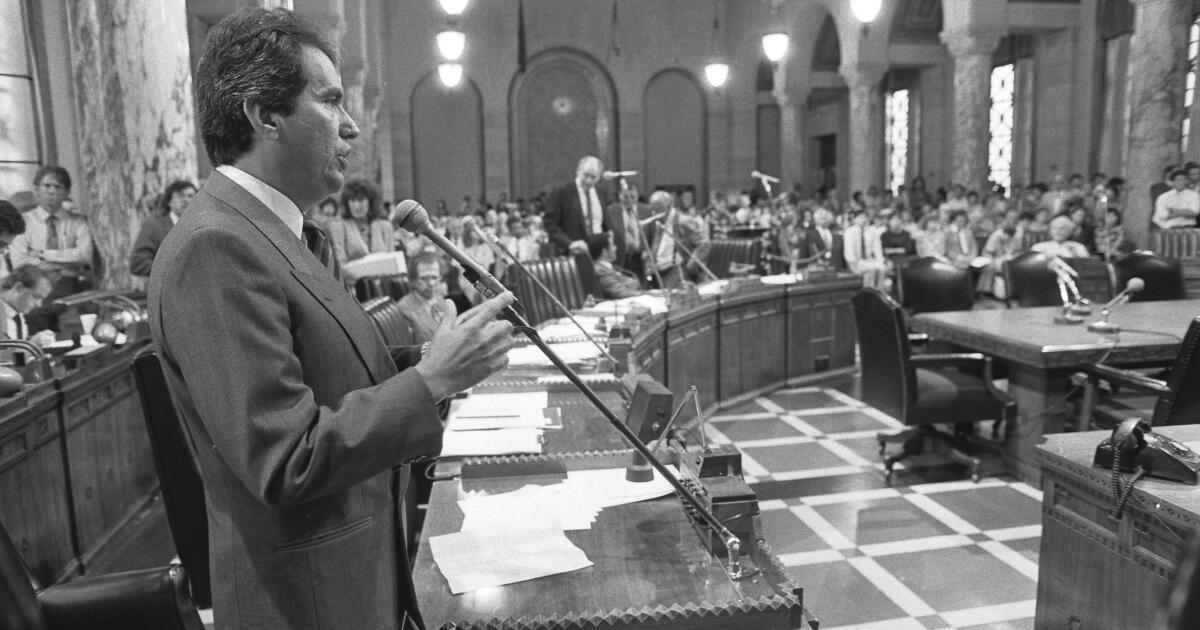

In 1985, Snyder announced he was resigning in the face of scandals. Alatorre easily won the special election to replace him. Hundreds of people, including Brown, then-Assemblymember Maxine Waters, Reps. Mervyn Dymally and Roybal, and Cesar Chavez, attended Alatorre’s swearing-in at City Hall, along with a serenading mariachi.

Alatorre was soon put in charge of redistricting council seats. His moves not only led to new boundaries that enabled Gloria Molina’s victory in 1987, but he also strengthened three districts held by Black council members since the 1960s so that they would remain Black-led for decades, a reality that remains true today.

“He felt every person in his district had dignity, every kid had a future, and everyone had hope,” said Hilary Norton, Alatorre’s former chief of staff, who remembered toy drives organized by Alatorre in his district. “He believed in God’s power to redeem everybody.”

Alatorre’s power continued to grow. He became the inaugural chair of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority board of directors, and helped Richard Riordan become mayor in 1993. His former staffer, Richard Polanco, became the head of the Latino Legislative Caucus and continued his mentor’s goal of getting more Latinos in public office. Critics alleged that Alatorre seemed too eager to direct city contracts to supporters — and he made no apologies for that.

“I didn’t establish the rules of the game. I just learned them well and know how to apply them,” he told The Times in 1999, just before leaving office. “Yet they [the press] write about how sinister that is.”

By then, the controversies that always lapped at Alatorre had subsumed his career.

While he was an assemblymember, the California attorney general’s office investigated him and other Latino politicians for alleged ties to the Mexican Mafia, which proved unfounded. Months after his historic city council win, Alatorrre paid a then-record penalty for illegally financing the race with funds from his assembly campaign. He was fined again in 1988 for trying to steer a city contract to The East Los Angeles Community Union, better known as TELACU, which had paid him a $1,000 speaking fee.

None of this tarnished his image among supporters or diluted his influence. But a 1996 lawsuit, filed by a former MTA employee alleging he was fired for opposing a $65 million Eastside subway contract that would partially benefit Alatorre associates, proved more corrosive.

Local and federal investigators began to look at everything from Alatorre’s votes as MTA board chair to charities he promoted to his purchase of a home in Eagle Rock and even who financed the retiling of that house’s roof.

Those investigations resulted in no charges. But the most damaging blow to Alatorre’s reputation happened in 1998, in the midst of a custody battle. The dying sister of Alatorre’s wife had signed over guardianship of her daughter to the Alatorres instead of the girl’s biological father, Henry Lozano, an Eastside political veteran who had helped on Alatorre’s first campaign.

In sworn testimony, Alatorre said he hadn’t used cocaine in years. But a month later, the presiding judge in the case ordered a surprise drug test. It came back positive.

A few months later, Alatorre announced he wouldn’t seek a fourth council term.

“I guess one of my shortcomings was not being able to help people define Richard Alatorre,” he complained to The Times in 1999 on his way out. “Everyone got caught up in my style, in the way I dress, the way I talk, not what I believe in … my enjoyment in helping others.”

Two years later, he pleaded guilty to tax evasion after failing to report nearly $42,000 in alleged bribes. He was sentenced to eight months of house arrest, allowed to leave only for grocery shopping or work.

“For five years, I had to wake up wondering what the next story was coming up,” Alatorre told L.A. CityBeat in 2005. “Because of what happened, I’m the sum of the end of my career, when things were bad. I’ve got that asterisk on my resume that overshadowed 28 years of work.”

By then, however, Alatorre was in the midst of a personal, professional and political comeback that continued for the rest of his life.

He found quick work as a consultant and lobbyist, sparking a 2010 investigation by the L.A. County District Attorney’s Office that concluded he did lobbying work without registering with City Hall but did not result in any charges. A new generation of Latino political hopefuls sought his advice, none more than Antonio Villaraigosa. The two had frequently clashed on the MTA board during the 1990s, when Alatorre was chair and Villaraigosa was Molina’s representative. By the time of Villaraigosa’s successful 2005 mayoral run, Alatorre was a key adviser and remained one until the end.

“He forgot more than I ever knew,” said Villaraigosa, who spoke earlier this year along with Mayor Karen Bass at a banquet at the Bonaventure Hotel in honor of Alatorre, who was too ill to attend. “Richard knew what needed to be done, and how to do it. He was never afraid to kick the door open when it needed to be.”

And while Alatorre’s failed cocaine test in 1998 sparked embarrassing headlines, he also credited the humiliation with “saving” him in his 2016 autobiography, “Change from the Inside.”

“With help from those I love the most,” he concluded in the 429-page book, with a photo of him surrounded by his beaming family on the opposite page, “I discover[ed] the power within me to find redemption and in the process for the first time in my life, I also [found] peace and grace.”

Alatorre is survived by his wife, Angie; their daughter Melinda; two sons from a previous marriage, Derrick and Darrell; and granddaughters Gabriela, Mariela, Daniela and Kaycee.