One of the reasons I stay on Twitter is that almost every day I’ll see a post from videogame auteur Hideo Kojima. Sometimes it’s a simple message that he’s listening to Joy Division again, sometimes it’s a few paragraphs about a movie he’s just seen and admired. (The month when he watched Furiosa like every day was especially fun). But sometimes he’ll post repeatedly about a certain actor he’s interested in—Norman Reedus, Mads Mikkelson, Lea Seydoux—and his followers will make jokes about how that person’s about to get Scanned. Not in the sense of Scanners, but in the sense that Kojima expresses his admiration by scanning actors and putting them into his games.

Show me a higher love.

One such actor was Hunter Schafer—and because I haven’t yet mustered the courage to watch Euphoria, this is my major point of knowledge about her. I went into Cuckoo with no idea what to expect, and was met with a raw, brutal performance, that is nothing short of extraordinary, and makes an already fun movie into much more than it could have been.

Cuckoo, while maybe not a perfect horror film, is gripping and surprising, and it did that thing I love where after I left the theater reality seemed brighter, sharper, less real—more like a movie set, and like anything might happen.

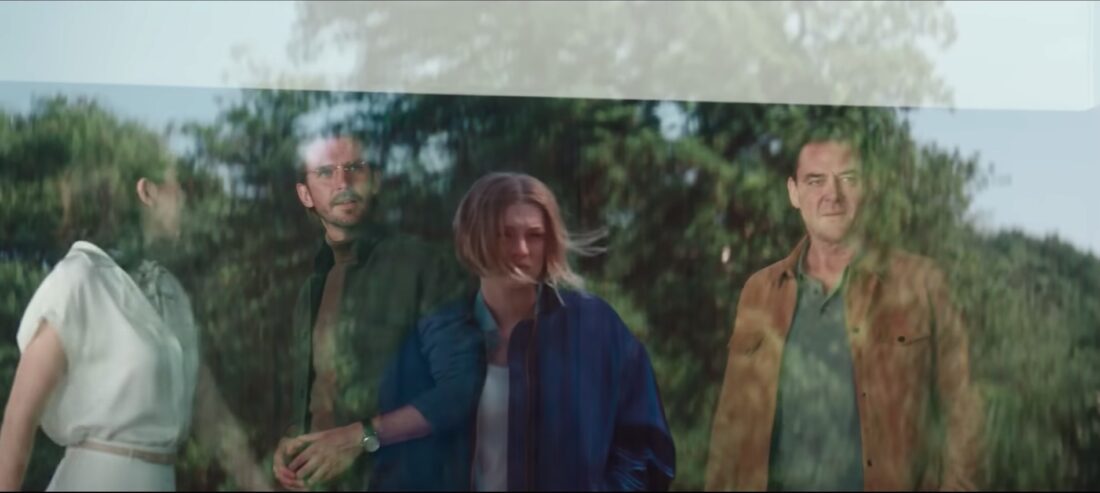

To get the details out of the way: Cuckoo was written and directed by Tilman Singer, the writer/director of 2018’s Luz. Schafer plays Gretchen, a teen musician who has recently lost her mother and gone to live with her dad Luis (Marton Csokas), stepmom Beth (Jessica Henwick), and stepsister Alma (Mila Lieu) in a resort in the Bavarian Alps. Luis and Beth are designing a new site for the resort property, and have a close (and unsettling!) relationship with the owner, Herr König, who is played by Dan Stevens. Dan Stevens (who I came to via The Man Who Invented Christmas and not Downton Abbey, because apparently I’m out of step with everything lately) gives an instant-classic horror performance that walks the line between frightening, really frightening, and fucking hilarious. Later in the film, Gretchen meets and develops very different relationships with Trixie (Greta Fernández) a resort worker, Ed (Àstrid Bergès-Frisbey), a resort guest, and Henry (Jan Bluthardt) a cop.

The film goes in a bunch of different directions (some obvious, some surprising), establishes its own world, sets a creepy tone that it mostly doesn’t break, and, most interesting to me, allows a lot of space and time for heartfelt emotions. What seemed on the surface like a fun, bonkers work of body horror instead becomes a surprisingly moving take on grief and family.

As horror, the film builds suspense and eeriness very early, and makes the smart move of keeping its scariest elements in shadows, dark corners, the-bathroom-stall-next-to-yours, rustling forests.

The adults all feel… the best way I can put it is “unnatural”? They all seem to be acting at a remove from reality, they all have hidden motives and agendas, and none of them can be trusted. The basic premise makes sense: the family is moving to a Bavarian resort so Beth and Luis can design a new wing. Who wouldn’t want to live in a mountain resort for a job? And of course Luis is going to bring his elder daughter with them—she hasn’t quite turned 18 yet, and she’s raw with grief. It makes sense that she’d join them here to heal, rather than live alone in the house she shared with her mom.

But obviously none of that is true. The resort is too isolated, and there are a lot of rules that make no sense. Why does everything have to be locked up by 10pm? Why doesn’t anyone work the desk after that—what if tourists come in later at night? Why do guests keep puking? If Luis wanted to help his daughter heal, he sure is being cold and standoffish toward her, and he sure does seem to blame her for his younger daughter’s health problems.

In the end the only adult who seems like a real, vital, person is Gretchen’s mom—who’s dead, and who we only hear as a voice on an answering machine message—but she still seems more accessible than Luis, Beth, Henry, or Herr König.

Like all good horror, there’s more going on beneath the surface. There are some interesting things about motherhood and childbirth, about men joining a conspiracy and lying to all the women in their lives, and about people thinking of women as breeding vessels rather than autonomous human beings—but ultimately the film just sort of gestures at those ideas rather than letting them weigh the tone down.

I don’t think I can say enough about Hunter Schafer in this role. Gretchen’s grief is a layer of magma under her anger at her father, resentment of Beth and Alma, amused discomfort for Herr König, and teen snottiness about being stuck in the resort that gradually grows into terror as reality shifts around her. Every single thing Schafer does feels true to me, and she’s in nearly every frame of the film, beaten up, bruised, in a cast, under threat.

So much of the film relies on parking a camera a couple inches in front of her face while she feels an inexpressible grief or terror. The film would not work, it would be a joke, if we didn’t believe her. But there wasn’t a second when I didn’t. As I’ve said in reviews, I don’t get scared usually, and I rarely cry. Cuckoo didn’t scare me, but I fucking well teared up a couple times.

The movie is also shot through with a really great vein of wacky humor. Dan Stevens pops up with unsettling German commentary, or creepy flute solos. There’s also, weirdly, a Die Hard gag that comes out of nowhere and made me howl.

There was a point when I thought the movie had veered in a really idiotic direction and blown its momentum—but no! That plot turn opened into another new direction, one that made the whole story work better than I’d even hoped.

I keep thinking about worldbuilding in the film (I spend a lot of time thinking about worldbuilding in horror in general) and on the one hand, I think an obvious critique of Cuckoo would be that there isn’t quite enough worldbuilding in it. The characters are dropped into an airless, closed, seemingly inescapable circle. As in all good horror, their behavior changes so slowly that they don’t notice it, even as the audience does, until the characters who should be the voices of reason are making choices that make no sense at all, and it’s left to the younger characters to see reality and respond. The “problem” is that the catalyst for this world, and for Herr König’s project, never quite makes sense. You just kind of have to go with it. And there were points when I was slightly annoyed that there weren’t more details like: how did this project start? How did Herr König learn about it? Why has he decided to do this, and what’s his endgame here?

But at the same time, I’m not sure that any of it matters, because now that I’ve sat with the film for a few days I think it works so well on emotional truth and dream logic that my questions don’t matter.

I promised myself no spoilers in this review, but there is one thing I have to talk about that will require spoilers, and that thing is Why I Think Cuckoo’s Ending Works Better Than Longlegs’. Which is obviously a bit of a spoiler! So if you haven’t seen both of those movies, and want to, skip the next few paragraphs and I’ll bold where you can come back.

I like Longlegs, but something about it has been bugging me—I don’t think the ending quite works. In the end, Lee Harker discovers that her entire life has been a lie, that her mother has been in cahoots with Longlegs, and literally Satan, who literally exists. And as Satan is in the process of killing her boss, her boss’ wife, and her boss’ kid, she’s able to interrupt the birthday party, kill her mother, and get the girl away from the haunted doll, seemingly saving her—at least in the short term, at least physically. But wouldn’t it have been more true (and more in line with the film’s brutal ‘70s aesthetic) to go for realism in this moment? Harker broken and distraught, the family dead, Satan ascendant?

I’ve been thinking about that ending for six weeks now, and Cuckoo’s ending is what finally snapped it into focus for me. Because Cuckoo is similarly concerned with disturbed men allying with supernatural forces to control the destinies of women and girls, but it also has a ludicrously happy ending, and the more I think about it the more I love it. When Gretchen realizes that she and her family are entangled in Herr König’s bonkers supernatural plot, it makes sense that she accepts it—she’s felt something was off the entire time they’ve been there, and has repeatedly, loudly pointed it out. She knows reality is wrong.

When she saves Alma, it makes sense—she and Beth have no relationship, her father half-assedly tries to comfort her, but overall treats her like garbage, but Alma wants to accept her as a big sister. It’s Gretchen who hates and resents her for reasons that have nothing to do with Alma as a person, and everything to do with their father rejecting Gretchen in favor of his younger daughter, and Alma still having a mom while Gretchen’s has died. So when Gretchen is faced with the reality of “I really am trapped in a supernatural plot, and it’s going to hurt my sister” it makes total emotional sense, to me anyway, that this grief-mad, lonely girl latches onto “I’M NOT GOING TO FUCKING LET YOU HURT MY SISTER”. The last twenty minutes or so of the film are her doing whatever she has to do to save Alma, while being realistically a human with multiple injuries and only a butterfly knife for protection. Her injuries ground her in a physical reality that makes the emotional reality of the movie that much stronger, and more moving. (And while I realize it might feel a little deus ex machina, the fact that Ed survives her injuries and shows up to rescue them is a wonderful queer girl cherry on top of the film, that balances out the absurd shoot-out between Herr König and Henry.)

OK YOU CAN COME BACK NOW I’VE STOPPED SPOILING THINGS.

I keep thinking of The Watchers, a movie I did not like, which had a few similarities—young people are trapped in an inescapable forest, older people have hidden knowledge that they use to control the younger people, there’s almost certainly supernatural shit afoot—but in that film I felt the reveal was too absurd and undercooked to land. It either needed to dive fully into the worldbuilding, and create a whole cosmology to hold the story, or lean into the unknowable uncanny to make the story more unsettling. Here, ultimately, I think Cuckoo does enough of the latter to save itself. We don’t have to know how or why, because the emotional arcs work so well, and the performances are so good, that the story creates its own world for us to fall into, and even when the plot gets wobbly Dan Stevens and Hunter Schafer are there to hold it up.